- the operator as client;

- an executive authority as representative of the legislature;

- an experienced, networked organisation such as ISSA Mining;

- a party responsible for tasks such as stocktaking, analysis, planning and implementation support;

- a party with technical and didactic capabilities of a theoretical and practical kind; and

- a manufacturer of relevant safety products, ranging from PPE to IT-based mine control rooms.

This article is based on a paper that the author presented at the 1st Vision Zero Europe Conference held in Bochum on 8th September 2016.

1 Introduction from the perspective of a German raw-materials industry expert

Raw materials are the first link in a widely ramified value-added chain and even in an age of growing globalisation they are an essential prerequisite for the functionality and long-term development and growth of national economies. The German coal industry also made a huge contribution in this area over many years, with the mining industries of the Saar and Ruhr coalfields playing a key role in Germany’s industrial and economic growth.

Even just a few decades ago, from a purely coal-industry viewpoint, this also applied to countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Spain. Coal companies were often the largest employers in the region concerned and the Ruhr Basin was one of the largest heavy-industry conurbations in the world. In Germany coal has for nearly 200 years been the main source of supply for the nation’s energy needs. Germany’s energy supply security therefore also depended to a large degree on the scientists and mining equipment suppliers. Over the course of these years the nation suffered its share of mining disasters and mourned the loss of many victims of these accidents. When analysed statistically in a graph of notifiable accidents the figures show how an ever greater safety awareness on the part of the workforce, combined with successive developments in mining techniques, machines, equipment and safety facilities, led to an ongoing improvement in safety standards.

In spite of its strategic and economic significance the Ruhr mining industry has repeatedly had to face difficult problems over recent decades. One of the most serious of these has been the persistently high and growing production costs that have been generated to a large degree by labour costs and social charges. It has not always been possible to offset these by increasing productivity. Neither technical innovations nor restructuring programmes produced the intended impact in the form of an improvement in the cost situation of the German coal industry vis-à-vis imports. An advanced environmental awareness in society at large, the ongoing development and growing use of alternative energies and, ultimately, the political decisions that were taken in 2007 have all played their part in ensuring that German coal production will be phased out completely, and in a socially acceptable manner, by the end of 2018.

Structural change in the Ruhr area did bring something by way of positive new business developments and also helped mark out a new economic landscape. The latter is now being comprehensively pursued with some interest and has been described as an example for other regions to follow. And so as history tends to repeat itself it is therefore likely that a similar pattern of change will play out in other mining countries too. But what needs to be emphasised at this point is that the German mining industry certainly does not end with coal!

2 Synergies in the mining suppliers sector require overseas partners

Raw-materials mining in Germany not only plays a key role when it comes to reliably supplying basic materials for the processing and manufacturing industries but at the same time has an important function as a catalyst for economic growth and employment. In 2016 the extractive industries, which strictly speaking means mineral mining, stone quarrying and sand and gravel extraction, employed over 90,000 people. This represents around 0.25 % of all German employees currently paying social security contributions. However, the actual impact on employment, including the effect on the upstream and downstream sectors of the economy, actually goes well beyond this. Without including the subsidised coal industry, a total of 58,084 people were directly employed in raw-materials mining, as an average figure, for the period 2008 to 2013. The overall employment effect of the raw-materials industry, including its indirect impact and other stimuli, is put at over 190,000 jobs. Every worker directly employed in the raw-materials sector accounts for 2.27 additional jobs in the wider economy (employment multiplier excluding coal), these resulting from the indirect demand for intermediate goods and capital goods and income-induced consumer demand (1). The consistently innovative segment that comprises small and medium-sized mining supplier companies, which has always been excluded from subsidies and other long-term measures of support, has for the most part been left to its own devices (Table 1). In 2016 the coal-industry supplier sector in North Rhine-Westphalia accounted for an estimated 8,000 to 9,000 jobs, while the opencast-lignite supplier industry provided some 1,000 to 2,000.

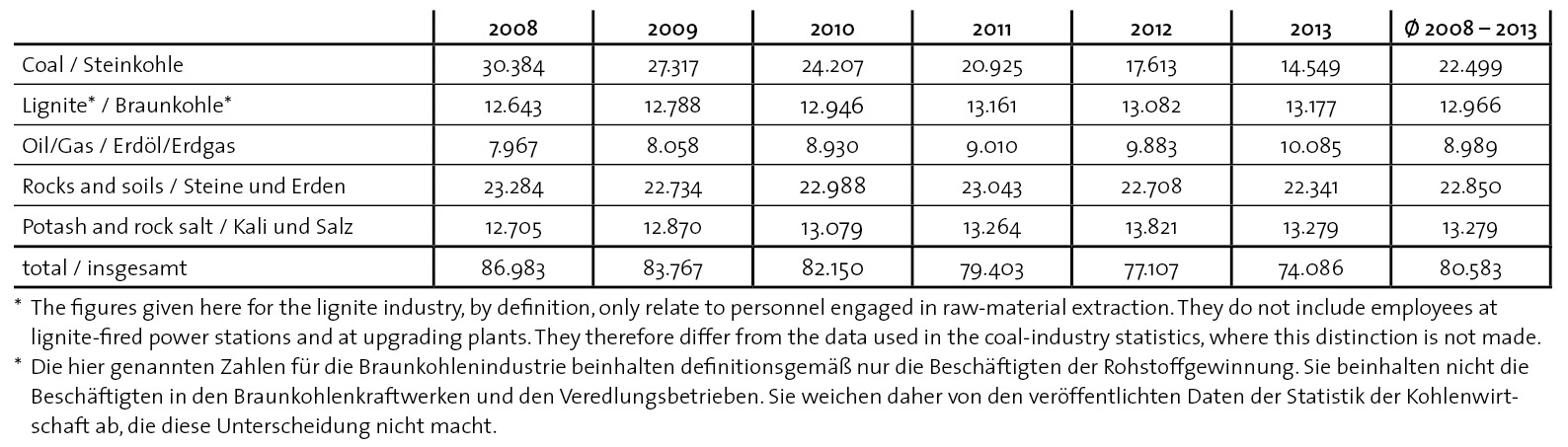

Table 1. Sector-based breakdown of the number of persons directly employed in the raw-materials extractive industries in Germany (1). // Tabelle 1. Direkt Beschäftigte in der rohstoffgewinnenden Industrie in Deutschland nach Branchen (1).

Overseas markets and other sales areas, which includes both conventional and new segment business, are absolutely vital for most specialist companies. The international market holds a huge number of potentially valuable customers, many of whom have set up new underground mining operations for the extraction of coal, metal ores, potassium and salt as well as for mineral production.

2.1 In retrospect

The management at mining equipment companies also embraced the mood of the day some 20 years ago or so as the number of mergers and takeovers increased worldwide with the opening-up of markets. Every manager ultimately hoped that by integrating skills, experience, capacity and even entire firms it would be possible to create something new that would deliver an even better performance.

A distinction soon established itself between cost synergies and sales synergies. Company expenditure may perhaps fall because economies of scale are being achieved, for example as a result of combined purchasing, or just one data centre is needed or – in the ideal case – managers and staff use or take over for their portfolio the best practice of the other company.

2.2 The current situation

The synergies between the mining companies and the suppliers are often weak or neglected, while those between the safety organisations and experts need to be improved.

At a time of low levels of innovation, high debt and low demand, factors that are paralysing the global economy, we need to seize upon every opportunity to support the export business if we are to cushion the impact of stagnation and recession, with the serious consequences this can have for the small and medium-sized enterprises in North Rhine-Westphalia. Transparent and communicative collaboration in mutual implementation makes alliances successful.

Example: Chile

The first step towards implementing potential synergies between Chile’s state-run and private mining undertakings and local companies, such as between the Antofagasta Industrial Association (AIA), which has more than 80 members, and the mining equipment supplier industry of North Rhine-Westphalia, were taken in November 2015 with the signing of a letter of intent (LoI) between the AIA and the EnergieAgentur.NRW mining network.

The intention to engage in some form of collaboration has existed for a number of years now. This includes cooperation between ISSA Mining and Mutual de Seguridad, university-level agreements such as that on knowledge sharing of the Technical University of Applied Sciences Georg Agricola (THGA) in Bochum or RWTH Aachen University, individual agreements between major companies in Germany and Chile and the German-Chilean Forum for Mining and Mineral Resources, which was set up in 2013 and is supported by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). Of course time will be needed to promote practical and dynamic developments based on these initiatives.

The capabilities of, and opportunities open to the individual members of the AIA, the companies from North Rhine-Westphalia and the customers in Chile are to be optimised by way of further contact, a process that will also be supported by the Competence Centre for Mining and Natural Resources of the German-Chilean Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the German Mineral Resources Agency DERA, the German Federation of International Mining and Mineral Resources (FAB) and VDMA Mining.

The downward trend in raw materials prices has meant that productivity has taken on much greater significance, even for the major companies like Codelco. Here it is only logical to exploit the synergy effects to the maximum degree.

Operating and production costs per tonne will provide a direct indication of whether synergy is increasing the efficiency of the company and reducing the costs. Cost cutting is in fact the fate of all mining companies if they are to survive in a period of economic downturn. Moreover, every measure adopted has to take account of the environment, the conservation of resources, sustainability and viability.

3 Some overseas starting points

3.1 The mining potential of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is keen to catch-up economically and the country’s rich mineral resources should make this possible. However, all this is still at a fairly early stage and many opportunities and risks lie ahead.

The local daily The Herald reported as follows on 2 June 2016: The synergy between manufacturers and the mining sector is at a low level. Mining and the mining industry must ultimately discuss things together rationally. This realisation comes from the Deputy Minister for Mines Fred Moyo. He went on to elaborate further that the link between the two sectors comprising mining companies and services for the mining industry was very weak and concluded that the mining industry, the suppliers and the manufacturing sector belonged directly together as virtually one unit and that these key economic areas accounted for nearly 30 % of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The government has stressed that the sector had to become active over the entire value-added chain, from exploration, project proposals, capital procurement, infrastructure and real estate through to the actual production of minerals, in order to create and sustain its competitive ability. And in this respect only safe companies could become good companies.

Zimbabwe has more than 40 individual mineral deposits, including coal, diamonds, nickel, copper, asbestos, gold and platinum, the latter constituting the second-largest reserves after those of South Africa.

3.2 The Chinese mining sector

While China is keen to get to grips with its emissions-related environmental problems, nevertheless coal is likely to retain a significant share of the energy mix for the next 20 to 30 years.

Since we started monitoring this market in the mid-1970s the intervening years have shown that China’s collieries are among the most dangerous in the world. Many of the 9,600 or so mines still in production are unsafe. However, the ‘accident rate per million tonnes produced’ has improved and unsafe and unproductive mines are being closed in their thousands. China is in fact taking safety issues very seriously and Japanese trainers have been in the country for a number of decades as part of a bilateral state programme. Since the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) began to make its presence felt in Beijing experts from Germany have also had an opportunity to apply their knowledge and abilities by way of a number of ‘train the trainer’ programmes. The large number of participants from senior management level, who come from provinces all over China, shows that this has been a useful and effective approach that over time will yield real improvements nationwide. What is still missing, for the next stage of the operation, are specific training measures for operational staff. The RAG-run Mining Training Centre (TZB) could provide some effective help in this area.

The low level of demand for coal in China contrasts with the huge overcapacity that has been built up over the previous 15 boom years.

3.3 The Indian mining sector

India is basing its future on coal and solid fuel is an integral part of the state-run poverty alleviation programme.

In 2015 and again in 2016 VDMA Mining and the Mining Network organised a roadshow to showcase the Indian raw-materials sector. The 2015 roadshow focused on coal and the 2016 event covered mineral ore. In terms of perspective coal is of particular interest, with more than one hundred new collieries on the drawing board in various federal states. Here too safety will play a major role, alongside other aspects such as machinery and equipment. Education and training is seen as a basis for development and under this motto preliminary talks are already underway with interested parties in India, namely Coal India und TATA, with a view to establishing permanent training centres similar to the TZB model referred-to above. The GIZ could also participate as a partner in this venture.

3.4 The Turkish mining sector

Turkey’s National Energy Development Plan, which covers the period to 2023, is based on coal production and the country has its mind set on becoming the largest coal producer in Europe.

The Mining Turkey trade show in November 2016, which was an exhibition of mining machinery and equipment, attracted a huge number of visitors and was one of the largest of its kind to be held in the country. Manufacturers had an opportunity to present their products and services to potential customers from all over the country. Items on display included: analysis instruments, mining vehicles and equipment, dewatering systems and pumps, conveyors, ventilation equipment, milling machines, separators, screens, explosives, deep drilling machines, crushers and so on. As well as being a showcase for mining products and services Mining Turkey also provides a forum for the discussion and analysis of new developments and future trends in the mining sector. EnergieAgentur.NRW also took part in one of the workshop events where mine safety was under the spotlight. The Soma mining disaster is still in everyone’s mind. Following this tragic event a whole series of industry contacts and initiatives took place. However, there are still no signs of a fundamental improvement in the daily routine and working practices of Turkish mineworkers nationwide.

The THGA, DMT GmbH & Co. KG, RAG, ISSA Mining and various companies including Siemag Tecberg, Bochumer Eisenhütte, Neuhäuser and others are now actively engaged in direct contact with the Turkish mining industry with a view to discussing problems and seeking solutions in the area of occupational safety, accident prevention and environment protection.

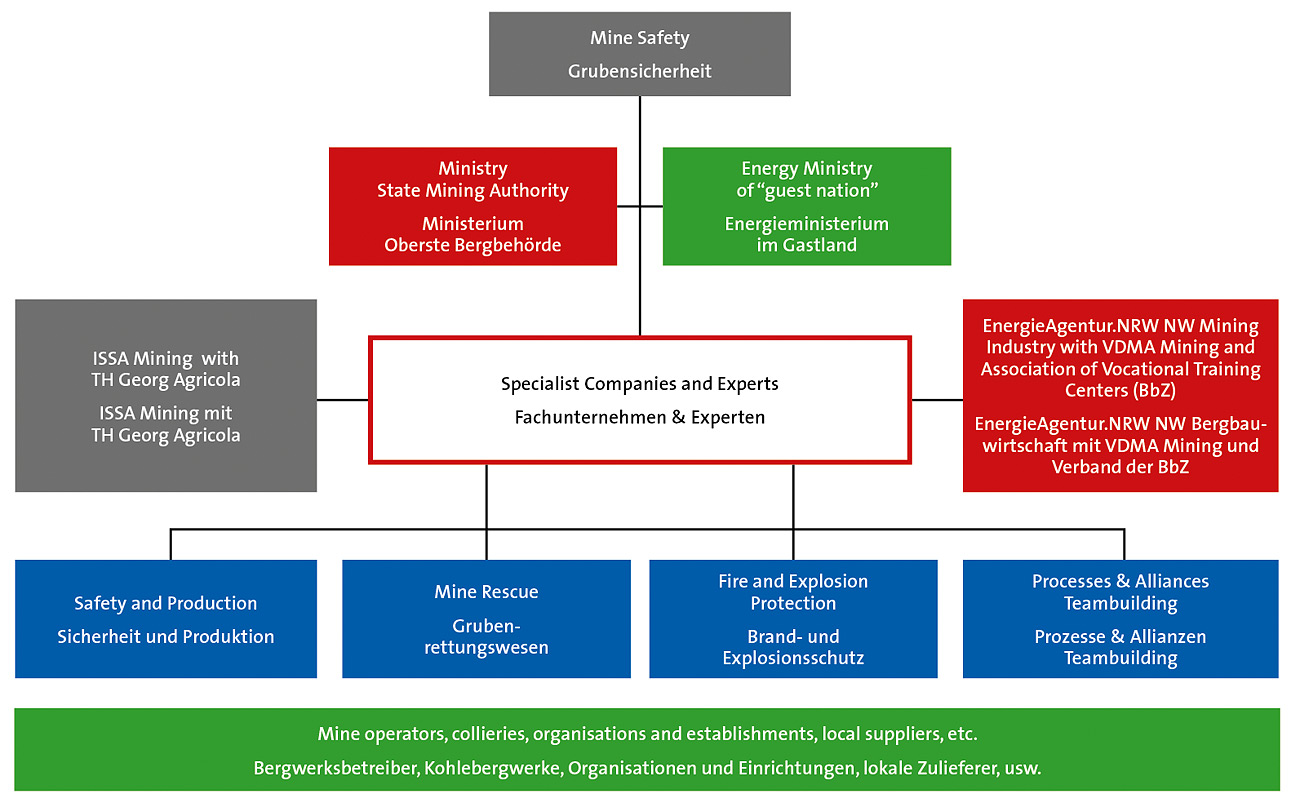

Figure 1 shows how German expertise can be exported to another country in order to implement an integrated safety policy.

Fig. 1. Safety concept based on German expertise. // Bild 1. Sicherheitskonzeption auf der Grundlage deutscher Expertise. Source/Quelle: EA

Teams of mines inspectors, consisting of geologists, miners, technicians, business managers and neutral coordinators, are deployed to undertake inspection visits. These mixed groups bring different skills to the table, with the result that all essential aspects can be taken into account leading to the fulfilment of compliance requirements. Equipment suppliers are also present on site in a sales-supporting role.

4 Building bridges between the domestic market and overseas

A company has to be safe and secure if it is to be a good employer and a reliable supplier of raw materials. While there is generally no disputing the key role that reliable and cost-effective supplies play when it comes to economic development, and while Germany’s present industrial infrastructure has over the years been very much shaped by specific raw materials-related factors, with the historic link between the indigenous coal production and the iron and steel industry being one prominent case in point, it is clear that domestic raw materials are simply not the focus of public attention. One major reason for the general lack of attention in this area is that this sector has to date rarely suffered from supply problems (1). In markets such as those referred-to above another situation prevails. Moreover, every raw-materials enterprise operating in the developing and emerging countries makes a contribution towards alleviating and eradicating poverty.

5 Exploiting synergies and finding realistic solutions

The ISSA Mining programme published under the motto ‘Vision Zero’ lays down seven concrete aims (2):

- to reduce the risk of industrial accidents;

- to cut down the number of new accident benefit claims;

- to reduce the number of fatal accidents at work;

- to lower the incidence of industrial diseases;

- to increase the number of accident-free workplaces;

- to introduce needs-based preventive programmes; and

- to increase the application of preventive programmes.

Many of North Rhine-Westphalia’s mining safety experts have years of experience in working for major mining companies, scientific establishments or testing institutes, where they were or still are responsible all kinds of issues to do with mine safety. Others have talents as innovative product developers. From sensors and measuring instruments through to mine support segments, all kinds of products are used in the manufacture of key components that have become indispensable for creating and maintaining a safe environment below ground. Each contributor therefore has his technical expertise and his implementation targets and will also have a sales market and potential customers in mind too. One will be an expert in mine gas extraction, another in risk assessment, while others will specialise in roadway arch supports or explosion protection.

One of the key tasks will be to demonstrate effectively and holistically to overseas specialists and their managers exactly what mine safety is and what is involved in creating a safe workplace. They need to know how to use and look after tools and machines properly and they have to learn where safety begins and to understand that it does not just end anywhere.

Safety is something that requires training and learning. It is particularly important to get across to the operational personnel that they need to adopt safe working practices and to look out for themselves and their colleagues. Basically, it is the job of trainers and mentors to create a spontaneous, self-advancing cycle.

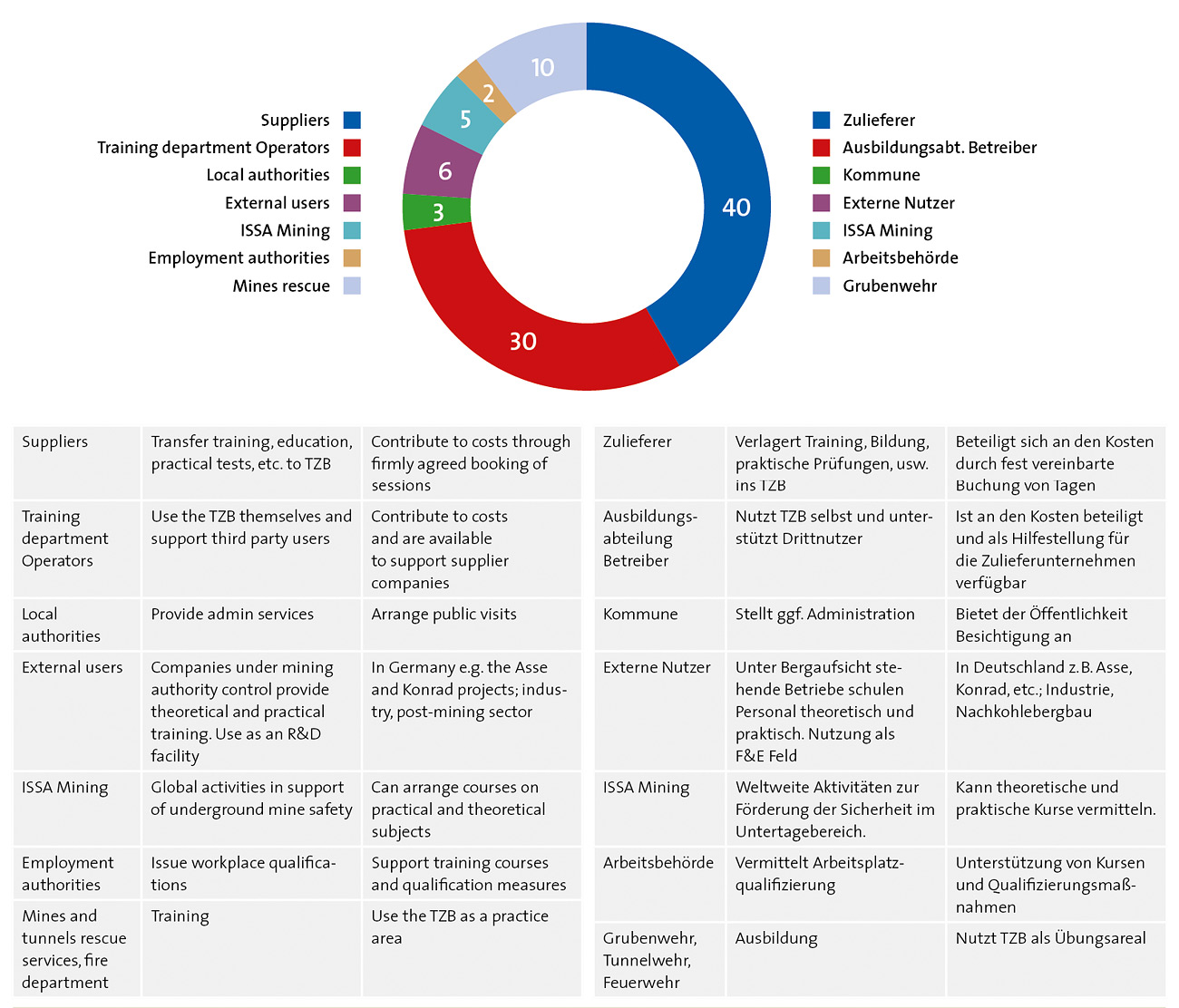

It is doubtful whether this can be achieved from just one source alone. Just as ‘mining is not a one-man operation’ so mine safety can only be created and maintained by acting together. Centrally drafted instructions are therefore needed of the kind communicated at a Mining Training Centre (TZB) with the motto of ISSA Mining at the entrance: ‘Vision zero. Stay healthy and safe with zero accidents’. Figure 2 shows the individual competences and performance areas that come together to produce an all-inclusive concept.

Fig. 2. Potential range of users for a Mining Training Centre (TZB). // Bild 2. Mögliche Nutzerverteilung für ein TZB. Source/Quelle: EA

6 Summary

Synergy is by definition integrally connected with the interworking of certain elements. It implies the optimal integration of something that previously existed separately. The synergy effect occurs through the association of elements. This is more profitable than the sum of the effects obtained from separately functioning sub-elements that are independent of one another. A symbolic description of synergy is obtained by using the formula 1 + 1 = 3. This concept highlights its positive effect. Synergy implies cooperation.

In a study carried out by the University of Zabrze (3) on behalf of the Upper Silesian Mining Authority positive synergy effects were effectively identified in the form of an improvement in efficiency levels and turnover profitability. The much-vaunted productivity did indeed improve. Here, such improvements in productivity are generally linked to increased capital commitment, such that the declining interdependence intensity of intermediate consumption is at least partly offset by an increased level of investment.

Comparable correlations also apply to labour productivity, an indicator that in recent years has seen continuous improvements not only in the German sector but in the Polish and Chilean raw-materials mining industries too. In this respect the macroeconomic significance of the raw-materials industry over time – as measured by the employment multiplier – will depend not only on the level of demand and on the interdependence intensity of business activity but also on own productivity improvements and consequently on the synergy effect.

As far as countries such Turkey, Vietnam, Indonesia and India are concerned these states can do best by investing in training as well as in research and development. Having better trained specialists and technicians will certainly be more conducive to the success of any planned investment projects in the raw-materials sector.

Occupational safety in the underground mining industry is and will remain an important factor in this context. Every stoppage, every malfunction and hence every interruption to the planned product flow will have a direct impact on the operating result.

Organisations such as ISSA Mining, scientific bodies and specialist companies and experts with experience in this area all lend their support to raw-materials enterprises at home and abroad. One of the main objectives must be for a collective effort to be made to identify the potential that exists in key areas so that all stakeholders together can contribute towards improving occupational health and safety standards in the industry.

References

References

(1) Vgl. Branchenanalyse Rohstoffindustrie. Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, www.boeckler.de, ISBN: 978-3-86593-222-8.

(2) Vision Zero; Die Präventionsstrategie der Berufsgenossenschaft Rohstoffe und chemische Industrie. www.bgrci.de

(3) Kowalska, I. J.: Synergy Effects in the Mergers of Coalmines. In: Zeitschrift Synergia, Zabrze. pp. 103 – 122; ijrs.umsc.lublin.pl/2016.