For Ruhrkohle and all its legal successors HSE not only means compliance with legal obligations but also constitutes a moral and ethical commitment that has now become an integral part of the corporate culture.

HSE is a subject that could fill several days of interesting and varied discussions. However, this paper only provides scope for a general overview of the developments that have taken place in the field of occupational health and safety at Ruhrkohle AG and its successor companies since 1969. The topic of environmental protection will not be dealt with here.

1 Introduction

For Ruhrkohle AG and all its legal successors up to and including RAG health, safety and environment protection (HSE) has not only meant compliance with legal obligations but has also constituted a moral and ethical commitment that has now become an integral part of the corporate culture. Before any kind of discussion of this subject can take place we need to provide a clear definition of what exactly is meant by “occupational safety”. This can then be followed by a review of the key issues that have affected health and safety developments from the year 1969 to the present day.

The most important aspect here is not the technology being used but rather the input in terms of management and organisation and of course the human factor. This includes the company’s policy on health and safety at work. Occupational medicine and health protection will form the second theme block and this subject will also be covered in this brief synopsis. Dust control has without doubt provided the main challenge to workplace health and safety and several technical examples will be used to highlight the efforts that RAG has made in this area.

2 Definition of terms

The Occupational Health and Safety Act defines the term “occupational safety” as follows:

“Occupational health and safety measures within the meaning of this act are those measures that seek to prevent accidents at work and work-related health risks, including those aimed at creating a humane working environment”.

RAG therefore uses the term “occupational safety” when referring to measures aimed at preventing accidents at work and “health protection” when referring to measures for preventing damage to human health.

If “management efforts”, rather than “technology”, is to be used as a criterion for examining the development of workplace safety at RAG it is possible to identify four distinct phases in this general process:

- Phase 1: 1969 to 1990

- Phase 2: 1991 to 2004

- Phase 3: 2005 to 2013

- Phase 4: from 2014 on

This survey will use as its guiding principle the various developments that have taken place in company policy on workplace safety and health protection over the years. The corporate objectives for occupational safety were drawn up soon after the establishment of Ruhrkohle AG and were laid down in Policy Directive BR 2/72.

“The corporate objectives are … to maintain and promote the health and productivity of the workforce and in this context to prevent damage to physical assets and avoid operational disruptions.”

3 Phases in the development of occupational health and safety

3.1 Phase 1: 1969 to 1990

Before Ruhrkohle AG was established the coal industry was plagued by serious accidents that resulted in many deaths and grave injuries. The main causes were firedamp explosions and mine fires. Technical measures in these early years therefore focused on preventing major incidents of this kind, which had such fatal consequences for the underground workforce.

Silicosis is a common disease among mineworkers. Lung disorders in the form of silicosis and chronic, obstructive bronchitis, or miner’s bronchitis, were long recognised to be typical ailments in the mining industry. Combatting these diseases was one of the challenges facing the health protection teams, with technical measures also very much to the fore in this area. Dust suppression therefore became a priority field of action.

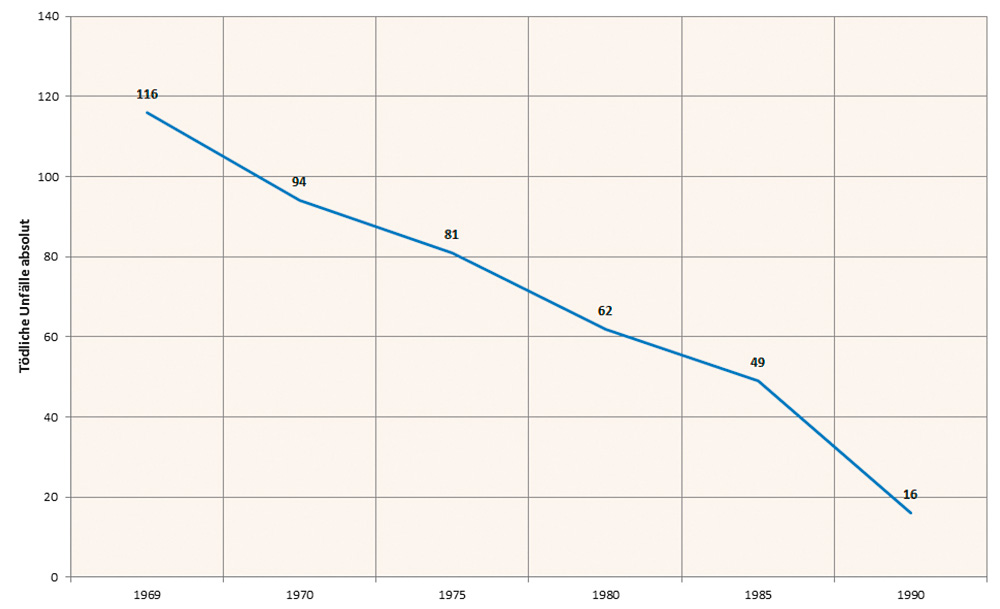

The figures for the number of fatal accidents in absolute terms, and the trend in accident rates in general, show that the measures introduced soon had a positive impact. The number of fatalities fell from 96 in 1970 to 16 in 1990. Most of these incidents involved individual accidents and it was rare for more than one person to be involved (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Trend line for fatal accidents recorded between 1970 and 1990. // Bild 1. Entwicklung tödlicher Unfälle von 1970 bis 1990.

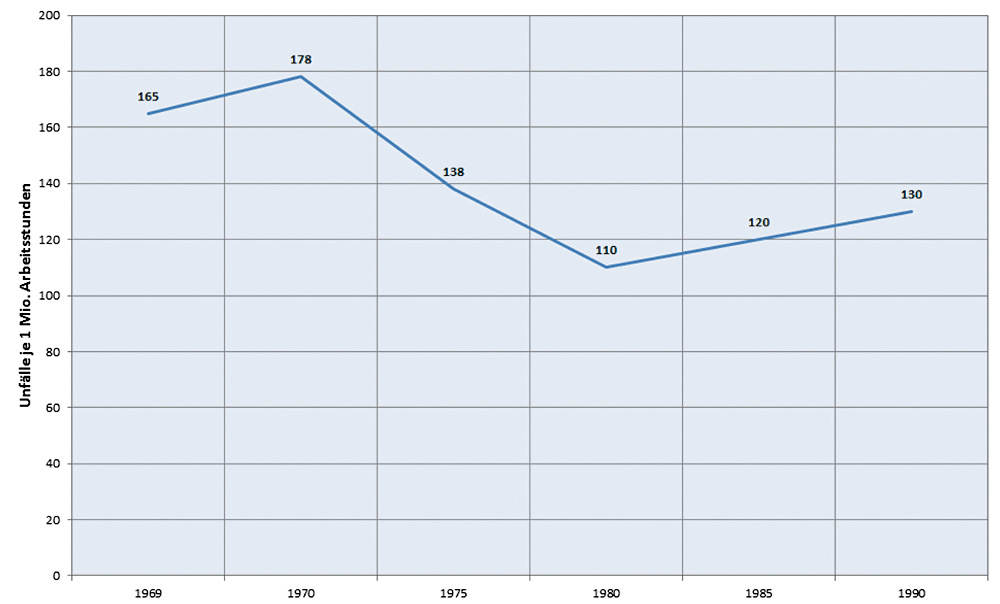

The accident rate was reduced from 165 accidents per million hours worked to 130 in 1990 (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Trends in accident rates for the period 1970 to 1990. // Bild 2. Entwicklung der Unfallkennziffer von 1970 bis 1990.

New mining legislation came into force in the early 1970s, namely the Mining Ordinance for Collieries in North Rhine-Westphalia (BVOSt) and the Mining Ordinance on Workplace Safety and Occupational Health Services (BVOASi).

An entire section of the BVOSt was devoted extensively and meticulously to a wide range of regulations on occupational health. The BVOASi defined the company’s obligations towards the establishment of an occupational health department with appropriate specialists whose numbers were contingent on the size of the workforce. Each occupational health service had to provide works doctors and medical assistants, as well as all the necessary facilities. The number of works doctors to be engaged was also clearly defined.

At this time statutory requirements and in-house rules led to the extensive introduction of “special officers”. Driven particularly by technical development, this process saw an increasing number of qualified personnel being delegated with special duties. This system introduced e. g. monorail officers for diesel trolley and rope-hauled installations, as well as belt-conveyor officers and so on.

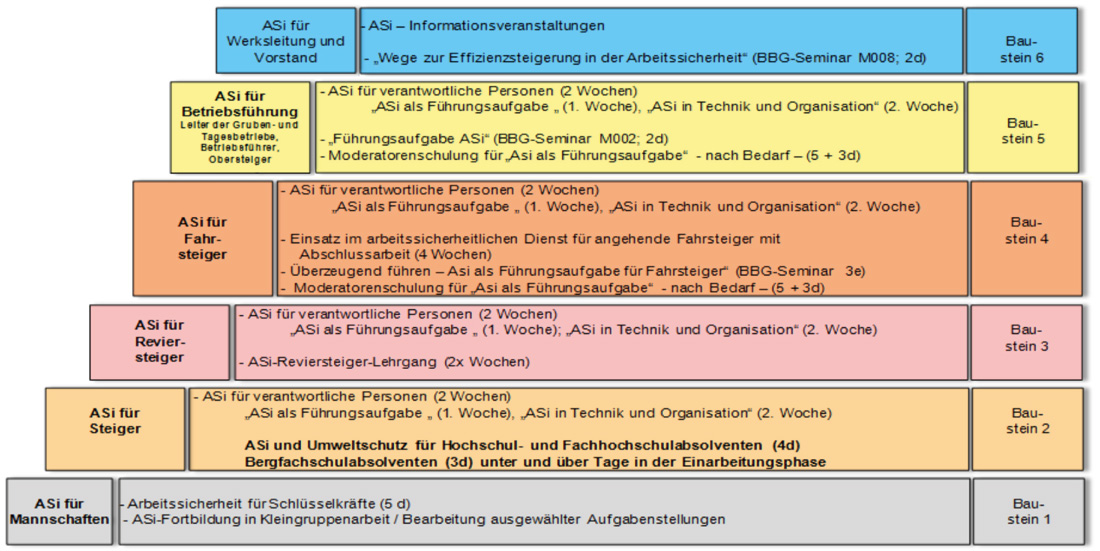

Occupational safety has always been a key concern for every member of the workforce and everyone involved continues to bear responsibility for themselves and for others. This realisation led to the development of the “ASi stairway” work-safety training scheme in the early 1990s. This system, with its six central elements, addressed every one of the company’s operating levels from level 1 “ASi for working teams” through to level 6 “ASi for management and executives” (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. The six-stage “ASi stairway” safety training scheme (1990). // Bild 3. 6-stufige ASi-Treppe von 1990.

3.2 Phase 2: 1991 to 2004

The beginning of the 1990s saw the development of “Ruhrkohle AG. The corporate mission statement”, an initiative that involved a large number of employees from every company level and department. This document is still referred to affectionately as the “goldfish” in reminiscence of the orange-coloured covers used for the brochure.

This document was aimed at improving and promoting the safety-conscious behaviour of everyone in the company and each and every employee was and would continue to be held responsible for maintaining safety and health protection at the workplace, both individually and for the workgroup. The safety awareness of every member of staff was to be encouraged and sustained through performance assessments and promotions.

The technology and procedures were continuously developed and refined. While the main focus was on coal winning and roadheading operations, significant progress was also achieved in the technical development of materials transport and product conveying equipment. Compliance with health and safety requirements remained a key factor in the procurement and introduction of new methods and equipment.

During this period the number of accidents resulting in fatal injuries fell dramatically. However, each fatality was still one too many. The number of notifiable accidents also continued to fall. The accident rate was reduced from 130 to 30 accidents per million hours worked. This trend could be regarded as evidence of a successful safety strategy: “We are on the right track!”

Mining regulations also continued to develop. These had to take account not only of developments in EU health and safety rules but also of measures being introduced into the German coal industry.

The General Federal Mining Ordinance came into force in 1995. This introduced for the first time an obligation on companies to draw up an occupational health and safety document – the SGD.

Then BVOSt and BVOASi were revised in early 2000. In the case of the BVOSt in particular this meant that the detailed rules on occupational safety in Section 2 were dramatically curtailed and then transposed into a new set of regulations, especially those relating to health protection.

The year 1996 saw the entry into force of the Social Security Statute Book VII. This also specified the employer’s obligations in respect of occupational safety, with § 22 introducing the concept of the “colliery safety delegate”, an honorary role to be performed by members of the workforce.

Technical equipment and organisational measures underwent continuous development, but this alone was not enough to meet the desired work-safety targets on a sustainable basis. Any further improvement in occupational safety and health protection could only be achieved by means of “human action”. Such a recognition meant that it was necessary to focus even more on raising awareness of the hazards and health risks posed at the workplace.

This led to the project “hazard awareness at the workplace”, whereby employees were to learn how to make a correct assessment of the hazards arising along the accident pathway: “In what kind of situation is the hazard being under- or overestimated in subjective terms?”

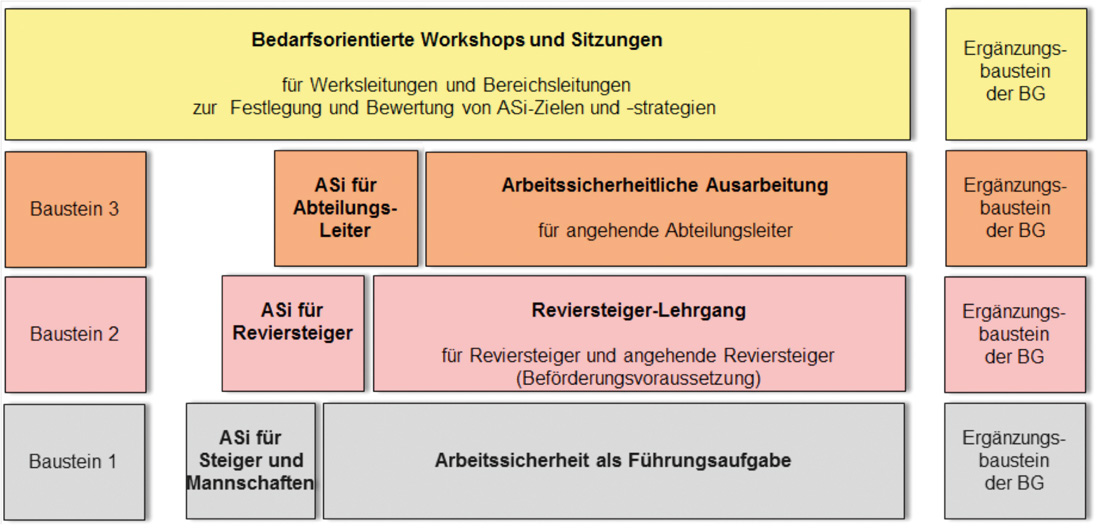

The ASi stairway “from the work teams to the management board” successfully supported the workplace safety efforts. After a high degree of participation had been achieved at all levels the development of professional training measures focused on the lower and middle management staff. These management grades have a close relationship with the workers and have a major influence on their safety behaviour (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Three-stage model of the “ASi stairway” (early 2000). // Bild 4. Dreistufiges Modell der ASi-Treppe Anfang der 2000er Jahre.

The internal system of work-safety indicators was extended to include absence parameters. The latter are intended to serve as a yardstick for the severity of an accident as based on the length of time that an employee is absent following an accident at work.

As the number of notifiable accidents continued to fall it became increasingly difficult to use these records for establishing core accident areas and from this to derive suitable measures for the prevention of workplace accidents and injuries of this kind. The analysis of accident patterns was therefore expanded to include an examination of the entries in the first-aid book. This analysis was based on the assumption that each entry in the first-aid book was to be treated as a “near miss”.

Company-wide employee surveys provided information on how in-house occupational safety and health protection was being perceived by the workforce. The resulting approval ratings were very high indeed.

Occupational safety and health protection are a management task. For this reason it was logical that key performance indicators should be used to ensure that this managerial responsibility was factored into the target system.

3.3 Phase 3: 2005 to 2013

The business sector in general was now starting to adopt all kinds of modern management tools, such as quality management systems, environmental protection management systems, lean processing and others. It was therefore logical that the wide-ranging actions deployed in the field of occupational health and safety – as initially introduced by RAG Deutsche Steinkohle AG – should be structured around the eight key points for developing and assessing proposals for safety management systems. These key points were developed by the Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs in collaboration with companies, associations, unions and social partners.

Examples of this initiative include:

- occupational safety policy and strategy;

- responsibility, tasks, powers;

- inclusion of safety and health protection in the operating processes; and

- performance calculation and assessment.

In 2011 the safety management system was rolled out over the entire RAG Group, with the new “Handbook for Occupational Safety and Health Protection” clearly recognising the growing importance of health protection and promotion.

Not a single fatal accident was recorded at RAG in 2005. However, between 2006 and 2012 the industry suffered a total of seven fatalities as a result of accidents below ground. There were none above ground during this period. There have been no further fatal accidents since 2013.

Accident rates continued to decline. The active involvement of the workforce in process organisation and hence in the safety efforts being made at operational level was clearly reaping rewards.

The development of commercially available IT applications meant that work safety and health protection documents, which had previously only been available in hardcopy form, could now be digitally produced and archived. Access to a central database meant that certain standards could be applied when drawing up risk assessments. This user-friendly system allowed personnel to be given better support in the performance of their routine statutory duties. This work was greatly facilitated by a wide range of dedicated functions, including the ability to track and follow-up deadlines.

3.4 Phase 4: from 2014 on

Zero accidents, no damage to health and no environmental damage – these are the environment, health and safety objectives that now guide and direct the RAG workforce. Our occupational safety policy can be defined as “Work safety comes before production. All commercial activity starts with health and safety!”

The figures speak for themselves. Unwavering commitment to workplace safety, deployment of optimum technology and procedures, good organisation and finally – the real key to success – the involvement of the entire workforce in shaping the process and their inclusion in the work-safety programme: this is what has helped the industry achieve these remarkable results.

Moreover, we have taken steps to ensure that as coal production comes to an end, and during the post-mining years to follow, all our employees will remain safe and healthy. With this aim in mind we launched an industry-wide campaign in 2016 under the slogan “Safety! – think safe before you start” that once again appealed directly to our employees and was intended to raise their awareness of the vital role that health and safety play in the day-to-day dealings of the RAG company.

The campaign motto is shown in Figure 5. The first five colours each stand for a common accident cause as identified by the company. The orange-coloured exclamation mark is representative of the corporate health-management process.

Fig. 5. “SAFETY! – think safe before you start”: slogan for the post-2015 workplace safety campaign. // Bild 5. Motto der Arbeitssicherheitskampagne ab 2015.

4 Health management and occupational medicine

4.1 Phase 1: 1969 to 1998

Occupational medical care was common practice in the coal industry of the 1950s and standards in this area were well above anything to be found in most business enterprises of the time. Medical care included initial medical checks and follow-up visits. This was aimed at identifying potential health problems as early as possible so that effective action could be taken. A priority objective was to support measures being implemented to combat work-related illnesses. The adoption of the Mining Ordinance of Health Protection then saw the introduction of past-exposure examinations. This scheme represented an important additional contribution to the medical aftercare of former mineworkers.

By working closely with colliery engineers, particularly on aspects relating to workplace safety, and with the aid of intensive medical research the industry’s medical services were able to make a significant contribution to combatting work-related health disorders. Technical and organisational measures meant that by the early 1980s no more cases of silicosis were being reported among active mineworkers.

Occupational medical research has operated alongside the health protection services since the 1960s. Much research work and many of the projects were aimed at combatting typical coalworker’s ailments. There were also new challenges to tackle in the later years.

The activities undertaken in this area have included:

- work on bronchitis among coal industry workers that led to it being recognised as an occupational disease, now designated BK 4111;

- the Saar cancer study;

- work on miner’s pneumoconiosis; and

- investigations into high-temperature mine climates.

Legislators reacted to the ongoing changes taking place in the coal industry by introducing a number of regulations. 1983 saw the adoption of a new Mining Ordinance to protect workers from adverse mine climate conditions (KlimaBergV). In 1991 a new Mining Ordinance on the protection of workers’ health came into force (GesBergV). These measures regulated occupational medical care and also contained special provisions relating to the deep mining industry. Here a key focus was on exposure to fibrogenic dust.

4.2 Phase 2: 1999 to 2008

In the mid-1970s the prevention element began to feature increasingly in the field of occupational health and safety. Here attention was focused on preventing potential hazards and health impairments arising in the first place.

A new field of action also opened up in addition to workplace safety and occupational medicine. This initiative was directed in a more targeted and specific way at individual employees. Specific care and support measures for employees were introduced at the end of 1999 as part of a works agreement at RAG DSK. An agreement on “corporate integration management” followed in 2007.

According to health insurance statistics musculoskeletal disorders were the most common cause of incapacity for work. The pilot project “working to prevent back problems” was the first to show staff the right way to lift and move loads. “Back work-out sessions” were introduced to teach the correct way to exercise the musculoskeletal system. This initiative can be considered as the birth of workplace health promotion at RAG Deutsche Steinkohle.

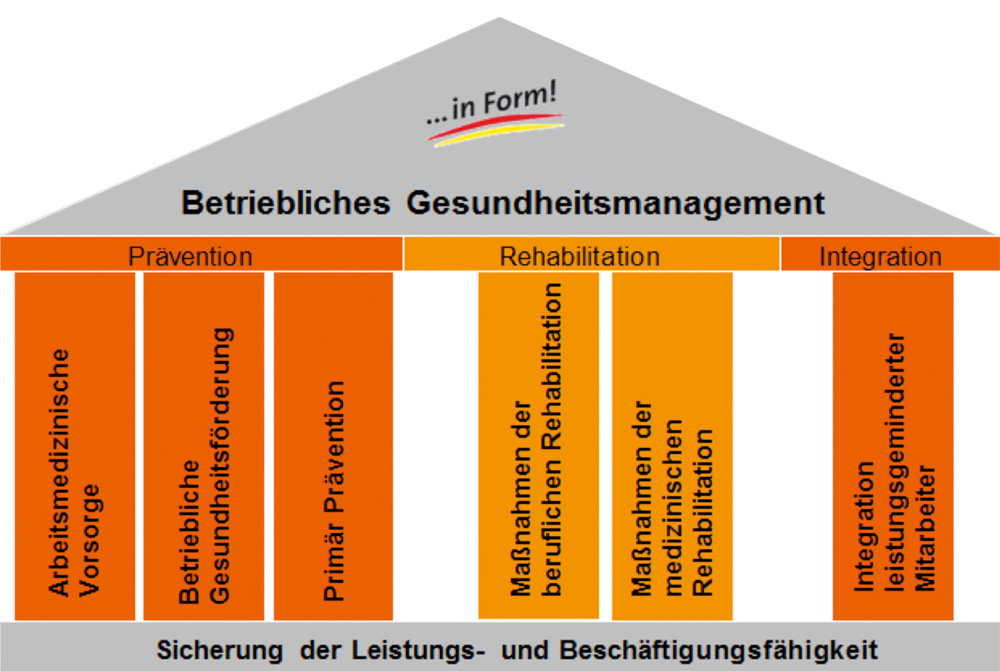

2009 finally saw the application of a holistic approach to “corporate health management (CHM)” at RAG. Figure 6 shows the strategic positioning of CHM as a temple structure with its three pillars – prevention, rehabilitation and integration. Corporate health management and promotion with its widening range of services was then rolled out over the entire RAG Group.

Fig. 6. Corporate health management – the temple model. // Bild 6. Betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement als Tempelmodell.

5 Selected examples of technical dust control measures

As already stated, the suppression of coal and stone dust has been one of the most important fields of activity for workplace safety and health protection throughout the entire corporate history of RAG, and indeed well before. The following presents in brief outline some of the technical solutions that have been adopted in this area.

Water infusion is of course one of the “classic” methods used at the coal face. This was practised both on the face itself as well as in the gate roads.

The primary objective was to bind the dust at its point of origin. Long-recognised techniques employed to this end include water sprays fitted to the drum bodies of coal shearers, cutter track spraying on plough faces and water spray systems incorporated into shield supports. Figure 7 shows the spray equipment fitted to a drum shearer loader.

Fig. 7. Dust suppression provided by spray jets on the shearer drum. // Bild 7. Staubbekämpfung mit Bedüsung der Schneidwalzen.

In roadway drivage operations it has been standard practice for many years to fit cutting-head spray systems to roadheading machines, while spray systems are now routinely installed for dust suppression purposes on impact crushers and at each transfer point along the coal conveying circuit. Dust extraction systems with filter technology have long been an integral part of the mine ventilation equipment employed in roadway drivage operations, especially in the case of selective-cut roadheading machines.

In areas with difficult ventilation conditions – where airflow speeds were high – some sections of belt conveyor were fitted with hoods to enclose the installation. At certain critical points dust extraction units would also be installed in order to control the make of dust. This was often the case at belt transfer points or at bunker intakes. In roadway drivages dust make was suppressed at the point of origin by employing wet-drilling equipment for the drill work.

6 Summary

Good health is the most valuable asset we have. This is something that is worth protecting. Occupational safety and health protection have always been one of the priorities for Ruhrkohle AG and this principle will be maintained by the company’s legal successors. Company policy has expressed this very clearly in all its facets.

Numerous measures taken over the last 50 years of the company’s history have contributed to unparalleled progress in this area:

- The figure of 94 fatal accidents recorded in 1970 has been reduced to zero every year since 2013.

- The accident rate of 165 per million hours worked has now fallen to a figure of 2.5.

- No new cases of silicosis among underground workers have been recorded since the beginning of the 1980s.

The key factors behind all these successes have been (and continue to be) the use of the latest technology, optimum procedures and practices and the direct involvement of each and every company employee.

I should now like to close this paper with two contemporary and yet timeless messages: “Safety! – think safe before you start” and “100% miners and mates – now and forever!”