1 Background

Near-surface geothermal activities have no direct connection with mining legislation and only drillings that go deeper than 100 m are considered in § 127 of the Federal Mining Act (BBergG), which throughout contains a reference to mining regulations. If this is not the case then a reference to mining law is only required for mining-relevant issues. Geothermy for the purpose of heating buildings is not such an issue (§ 4 para. 2(1) of the BBergG). The preliminary question therefore relates to the rele-vance of mining law. This is also very much dependent on the type of liability regime that applies – in other words is it mining liability (§§ 114 ff. BBergG) or general damage liability as defined in § 823 of the German Civil Code (BGB) of the kind that applied in the Staufen incident, where water penetrated a sub-surface layer of anhydrite, resulting in ground swelling and a large number of cracked buildings.

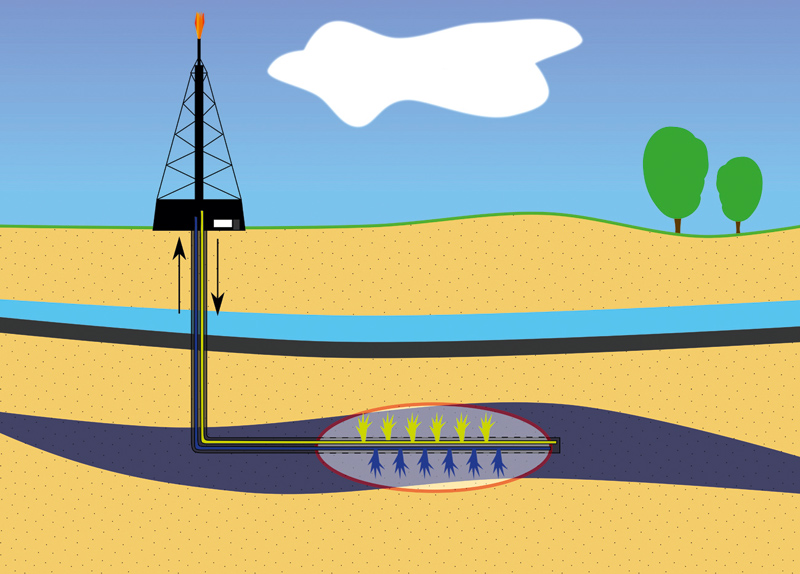

There are also additional influencing factors arising against the backdrop of the latest hydraulic fracturing legislation. This part-modified and now adopted legislative package (1) specifically covers boreholes insofar as liability for mining subsidence is concerned and also allows the presumption of mining-related damage to intercede in connection with these wellbores. Conversely, geothermal boreholes that are connected with fracking operations are part of the related regime (§ 9 para. 2(3) of the Federal Water Resources Act (WHG)). This applies in particular to petrothermal procedures where at least two wells are drilled so that fractures can be generated in a targeted way (fracks) and by this means a water-permeable connection can be created in the rock (2). A moratorium on these practices has been in existence for some time.

2 Relevance of Mining Law

2.1 Only in the case of non property-related extraction

According to § 3 para. 3(2(2)) of the BBergG geothermal heat constitutes a freely mineable resource. However, § 3 para. 2(2) of the same BBergG also states that ownership of a piece of land shall not extend to freely mineable resources. Consequently, and in accordance with § 6 of the BBergG, an extraction licence or mining permit shall be required for such purposes (3). Yet, in the absence of extraction according to § 4 para. 2(1) of the BBergG this shall not apply insofar as the recovery of geothermal heat is related to a piece of property and is therefore, e. g., undertaken for the purpose of heating a building. This provision particularly excludes the stripping or releasing of resources on a piece of property during or in connection with its exploitation for construction or for some other urban development purpose. Such “freedom from mining rights” is in some instances extended to cover all boreholes drilled on private property that do not go down deeper than 100 m, provided that no commercial usage ensues and there is no impact on the temperature conditions prevailing on the neighbouring plot, and that consequently the energy status of the latter’s ground is not affected in any way (4).

This latter disposition also means, conversely, that because extraction activities are involved, a mining permit is required if the said activities have a commercial purpose rather than a private one. According to the legal wording of § 4 para. 2(1) of the BBergG such a permit shall always be required if the purpose of the geothermal activity is not restricted to the constructional or other urban development usage of the piece of property on which the extraction work is carried out. The recovery of geothermal heat goes beyond this if it contributes to the heating of buildings on other properties and if the latter have no direct spatial or operational relationship to the property that is the site of the extraction, or if the geothermal heat is to be used for the production of electricity or community heating and is to be fed into the general supply network (5). In this respect, even a commercial usage will fall outside the scope of mining law if it is purely property related and serves for the heating of business premises on the entrepreneur’s own land.

As a result it does not come down to any hydrological or geothermal impact on neighbouring properties (5). The BBergG makes no restrictive declarations in this regard. The formal approach that relates purely to the use of the entrepreneur’s own property is also to be preferred because it ties in with the circumstances that pertained at the outset, whereas the question of any potential impact on neighbouring plots calls for a prognosis whose outcome can also be uncertain.

2.2 Commercial and scientific exploration

Activities that are aimed exclusively and directly at teaching or instruction are also excluded from the requirement for a mining permit. These activities are exempted under the meaning of exp loration in accordance with § 4 para. 1(1(2)) of the BBergG. If the said activities extend beyond mere teaching and instruction, a commercial and a scientific licence may be applicable (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Since October 2012 the RAG company has been working with the Bochum municipal utilities on a joint thermal energy project that will use mine water extracted from the now closed Robert Müser colliery to provide climate-friendly heating to three public buildings (two schools and the main station of the Bochum fire brigade). // Bild 1. Zusammen mit den Stadtwerken Bochum nutzt die RAG Aktiengesellschaft in Bochum-Werne seit Oktober 2012 Grubenwasser aus der stillgelegten Zeche Robert Müser, um drei Gebäude klimaschonend zu beheizen (zwei Schulen und die Hauptwache der Bochumer Feuerwehr). Photo/Foto: RAG

Exploration according to the terms of the BBergG shall not include the underlying aims and the subjective purpose of the activity, and hence not its ultimate and final goal, so that exploration for scientific purposes also comes into consideration as well as that which has a commercial objective (6). Whether or not the natural resource in question is commercially required and indeed subsequently extracted is not initially relevant to the case in question (7).

2.3 Storage and extraction of heat energy

Apart from specified purposes, certain operations are not subject to mining law. This applies, e. g., to the admission of heat energy into the ground so that it can be stored and then extracted at some future date. In this respect, there is also no relevant legal situation in respect of containerless deep-level storage. However, if over the longer term more heat energy is extracted overall from the substrate than is originally introduced, the application of mining law is to be examined irrespective of the derogation clause at § 4 para. 2(1) of the BBergG.

2.4 Wellbores

2.4.1 Inclusion of boreholes more than 100 m in depth

The drilling of boreholes constitutes a classic mining activity (Figure 2). In many cases these wells are already included and covered by mining permits irrespective of their depth. This also applies to geothermal energy operations when these constitute a mining activity, as this is not purely property related. In other respects the inclusion of geothermal boreholes into the mining regime will depend to a large extent on their depth. If in connection with an operation to extract heat energy that is not in itself subject to mining law such wells should exceed 100 m in depth, notification of this fact has to be given to the mining authorities in compliance with § 127 of the BBergG. This authority will then decide whether an operating plan is required in accordance with §§ 51 ff. of the Act, either because the operation has a certain significance or with a view to the protection of employees and/or third parties.

If the borehole exceeds 100 m in depth, it is also possible that the mining authorities will in a particular case impose on the entrepreneur a duty to maintain an operating plan (§ 127 para. 1(2) of the BBergG). This does not therefore apply as a general rule but rather only in justified cases, such as when particular hazards are present that could compromise the health of third parties, or when the operation in question is of particular significance. Cases of this kind would exist, e. g., when drilling is being carried out through strata that are in contact with groundwater or when there is a risk of encountering water resources that could then penetrate a critical bed of rock and cause the ground to swell up, as indeed happened at Staufen.

2.4.2 References to water law

Should one of these grounds apply, and if as a result an operating plan procedure has to be implemented, other relevant authorities will also be involved in the matter in accordance with §§ 55 ff. of the BBergG. However, a special water law permit will still be required. This can in fact be granted by the mining authority, in accordance with § 19 para. 2 of the WHG, and not as in other cases by the water authorities, and is routinely issued along with the permit authorising the operating plan. In cases involving an obligation to implement an operating plan it is also necessary to refer to the judgements of the BBergG, especially where liability is concerned. The requirements that apply under mining law also have to be observed when, in the absence of an operational planning obligation, a water authority is deemed to be the responsible body (8).

In either case water legislation provisions shall determine whether a permit is required under water law (9). The decisive factor, according to § 9 para. 2(2) of the WHG, is ultimately whether the geothermal wellbore is likely to have a detrimental impact on the water quality, either permanently or to a significant degree, and therefore constitutes what is referred to as improper use of the water body.

The duty of disclosure as specified in § 49 para. 1 of the WHG, however, is not seen as applicable when it comes to mining activities and other measures where a licensing and notification requirement does exist according to other legislative provisions, namely the Federal Mining Act (10). The duty of disclosure according to § 127 of the BBergG therefore takes precedence, while § 49 para. 1 of the WHG only applies thereafter for wellbores less than 100 m in depth.

2.4.3 Consequences and implications for liability

However, § 127 of the BBergG makes no reference to subsidence liability as covered under §§ 114 ff. of the Act. It is therefore intrinsically excluded on that basis, as the BBergG only mentions certain specific provisions in this context. Here it is the correlate of the potential danger presented by mining operations, a hazard that the individual has to accept and that can result in personal injury. This potential hazard finds expression in the statutory operating planning procedure and in the supervision provided by the mining authorities in accordance with §§ 69 ff. of the BBergG. These provisions also take effect in the case of wells that are deeper than 100 m where these are of special significance or present a certain risk. Mining subsidence liability only represents the final component in a comprehensive package of protection measures. This suggests that it should be part of the process too, or at least that its judgements should be applied to general civil liability.

With the law on fracking the presumption of subsidence damage in § 120 of the BBergG should also be extended to borehole mining activities (11). The existence of a borehole will thereby be linked to mining. Wellbores will not therefore be included in their entirety. If anything, these are not in any case covered a priori under the presumption of subsidence damage. In fact, this only serves to maintain and establish the distinction between boreholes drilled for mining purposes and ordinary wellbores, that is to say those intended for purely property-related and private use.

Fig. 3. Structural crack between the Town Hall and the Town Hall café in Staufen caused by ground uplift resulting from groundwater penetration. // Bild 3. Riss zwischen Rathaus und Rathaus-Café in Staufen aufgrund von Bodenhebungen durch eindringendes Grundwasser. Photo/Foto: Ekem

As drilling and extraction are very closely linked and interrelated, any separation here is purely artificial. The rules on legal liability under mining law, as outlined below, also provide indications as to who should provide liability under § 823 of the German Civil Code (BGB) when an operation aimed at recovering geothermal heat is preceded by the drilling of a borehole, the latter not however being covered by the provisions of the BBergG and only being subject to liability in respect of the breaching of the legal duty to maintain safety in accordance with § 823 para. 1 of the BGB. In many cases the implications resulting from such a wellbore only appear at some later date in the course of the (subsequent) extraction phase.

No rules on liability under mining law have yet been developed specifically for the extraction of geothermal heat. However, if as in the case of the Staufen incident (Figure 3) there is a penetration of groundwater followed by ground uplift resulting in surface damage. A parallel problem arises in terms of the question of who is legally liable when coal mining activities cause a rise in the groundwater level and cellars and basements are flooded. In both cases the damage is attributable to an inflow of groundwater, which poses the question of reasonable causality between the event and a preceding mining or geothermy-related activity. The highest courts in the land have so far rejected the idea that a local authority can have an action brought against it under state liability if it has identified a residential district in which houses have suffered wet basements due to a subsequent rise-back in groundwater levels (12).

3 Liability under mining law for damage caused by geothermal drilling

3.1 Drilling

According to the civil liability referred to under § 114 of the BBergG mining companies are to be held liable for any material damage and bodily injury “resulting from the exercise” of a mining activity. No culpability is required. There is a presumption of subsidence damage under § 120 of the BBergG, though this only applies to the area affected by underground exploration and extraction activities, and thereby to subsidence, compression, rupture and fissuring at the surface, and as of now also to well drilling activities, but not to water rise-back or uplift.

The cessation of water pumping operations marks the end of the mining industry’s involvement in the regulation of groundwater levels. This also applies to the impact of geothermal drilling, if such activities are followed by water rising up or entering an upper soil layer, with the latter then becoming completely saturated and causing ground heave. There is then essentially a need for water pumping measures. If this operation is halted or completely neglected, the process is attributable to operational events associated with a previous activity, even if it only results in the groundwater returning to its earlier level. Indeed the latter would never have been altered without mining-related influences. This can have far-reaching knock-on effects on adjoining property and even on more remote pieces of land within the water catchment areas, consequences that are directly linked to the way in which the land has been shaped by the local mining industry. This intrinsically related effect means that these areas are subject to liability for mining subsidence. This applies even more when the original water level is exceeded or if, during a geothermal drilling operation, water enters a layer of soil that was previously protected against such an ingress.

3.2 Causality

The prerequisite for liability is that the damage can be attributed to mining activities. This causal relationship requires that the damage is the direct or indirect consequence of mining operations (13). The extraction of natural resources is often not possible without causing a lowering of the groundwater level. This lowering process is then brought about by deliberate action, the rise-back being the counter-reaction to this. However, this latter process is not induced artificially but rather comes about by natural means. The same applies when, following a geothermal drilling operation, water accumulates and enters a layer of soil, thereby causing it to rise up, which in turn leads to cracks forming in the surface buildings. Natural causality therefore appears questionable at first sight (14). In any case an appropriate causation is rejected in the case of groundwater rise-back because here it is merely the natural status being restored (15). However, ground heave due to water penetration as a result of geothermal drilling, as happened in Staufen, is a different case in point.

This causal relationship can be severed in the case of a building development, e. g., if the latter has been improperly and incompetently managed. This can result from an inadequate assessment of the extent to which the groundwater can rise to its previous level, which is something that the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court has been asking building developers and architects to consider retrospectively for 30 years (16).

We are still awaiting resolution of the question of whether or not it is quite exceptional, and hence not sufficiently causative, that a geothermal borehole should result in water ingress and ground heave that eventually leads to the development of structural cracks and fissures. Of relevance here is the extent to which the subsurface should be surveyed in advance in order to investigate and eliminate such a train of events. Failing that, anyone contemplating a geothermal drilling project would only have to turn a blind eye and neglect any type of preliminary inspection in order not to be subsequently held liable for any loss or damage. Everything therefore essentially comes down to the objective facts of the situation, on the basis of which, after reasonable reflection and in the normal course of events, any loss or damage will be virtually excluded.

Examples that relate to the impact on bodies of water illustrate the extent to which a causal relationship can be established on the basis of adequacy theory, while also taking account of indirect causal connections. In this context the former German Supreme Court previously affirmed the causal relationship that was deemed to exist when mining activities caused the collapse of an underground conduit, resulting in the lowering of the water level in an adjacent lake, the outflows of which ended in a watercourse that ultimately served as a source of industrial water for a factory (17).

This shows that even quite remote influences can be brought into play via several different stations, provided that all can be traced back to mining activities. In the case of geothermal boreholes it is sufficient that these have proved to be contributory to the event and have only triggered a pre-existing development, thereby allowing a body of water that was previously inhibited to intrude owing to the composition of an adjoining bed.

3.3 Social adequacy

Where the mining company has followed its operating plan to the letter this does not automatically establish the socially adequacy of its conduct, this latter factor potentially serving as a basis for rejecting an adequate causal relationship. Liability for subsidence damage also constitutes strict liability and the latter takes effect even when the obligations under mining law have been met, the reason being that mining is a hazardous activity. The operating plans drawn up to facilitate projects of this kind cannot entirely prevent damaging consequences. In fact such occurrences are assumed to be inherent. As far as liability under mining law is concerned it is therefore immaterial whether the damage has occurred as a result of lawful or of wrongful actions on the part of the mining company (18).

3.4 Protective purpose

The adequacy assessment is to be supplemented by an evaluative appraisal based on the protective purpose of the standard. This very clearly requires an adequate reference to mining activity (19). However this will also largely be established for the pollution of water courses, which is a natural process that is facilitated and ultimately initiated by mining activities (20). This is also eventually what happens in respect of infiltrating groundwater that prior to the drilling operation was retained by a layer of soil that can become fully saturated.

As far as mining is concerned it also has to be generally taken into consideration that a certain degree of risk is intrinsic to this activity. Consequently, all processes that are connected with the conditions and realities of mining operations, and that exhibit a certain susceptibility to damage, essentially have to be regarded as included in the protective purpose of mining-related norms and standards. The mining entrepreneur therefore has to ensure that no danger is posed by the installations that he has created and put into operation. After all, he has established them and is therefore responsible for neutralising any potential risk that they present.

The owner of an ore mine, e. g., also has to implement safeguards against acid water, even though in his view the detrimental effects that have to be averted were in no way caused by his operations (21). In the Meggen ruling the mine operator was required to dewater the mine because of the ingress of groundwater and joint water, the aim being to prevent any mixing and diffusion of the heavy-metal concentrations (22). Water pumping and water pollution control are therefore an essential part of the mining operation and any omission or cessation of this activity will itself constitute an operating risk that will cause water levels to rise and ultimately present a threat to any buildings and dwellings located in the influence zone. This applies especially in the immediate aftermath of a geothermal drilling operation when water is able to infiltrate a receptive layer of soil and cause the ground surface to lift.

4 Operating plan requirement

Where the geothermal drilling forms part of a mining operation an operating plan will be required in accordance with § 51 para. 1 of the BBergG (23). This requirement also exists when mandated by the mining authorities on the basis of § 127 of the BBergG. However, no general operating plan is specifically stipulated for geothermal boreholes. The ordinance on the environmental impact assessment of mining projects (UVP-V Bergbau) does not contain any provision in this regard. Where no general operating plan is required, as outlined in § 52 para. 2a of the BBergG, a main operating plan is deemed sufficient. The latter shall be prepared on a regular basis for a period of two years, as stipulated at § 52 para. 1 of the BBergG, though may also run for five years if the activity in question is not dynamic in nature. In the case of geothermal boreholes problems can indeed arise if the rock proves to be somewhat different from that which was predicted by the geotechnical investigations. However, geothermal drilling is not an activity where planning has to be regularly adapted at frequent intervals, as is the case in coal mining, e. g., where the operating parameters and geological formations cannot be predicted with real accuracy.

If the drilling is being carried out in connection with an authorised exploration project, it requires a main operating plan before any work can commence. This is also to be expected when a programme of work has been submitted as a basis for the exploration permit, so that further confirmation might be provided that the borehole in question is not part of an exploration project but is only intended, e. g., for teaching and instruction purposes. A more detailed description is also required as to the scope of the geothermal exploration project, the technology being applied and the duration of the work. Evidence also has to be provided that the requirements laid down in § 55 para. 1(1(1)) and 3(13) of the BBergG have been met and that the exploration does not conflict with overriding public interest in accordance with § 48 para. 2 of the Act.

Here it has to be demonstrated in particular that the necessary precautions have been put in place to protect the health of third parties and consequently that the drilling of boreholes does not generally pose a health risk. With regard to the West Colliery ruling it also has to be stated that the groundwater will not be disturbed in any way that could have a negative impact on human health. Neither should such a negative outcome be possible at any point in the future. In any case water management concerns have relevance within the scope of § 48 para. 2 of the BBergG. However they only have to be complied with as such. A detailed verification of this is subject to water legislation permit (24). Such concerns do not stand in the way as long as a geothermal borehole is sufficiently shielded by impermeable rock beds and a continuous and reliable monitoring regime is put in place.

Immission protection regulations are also met when any buildings in the area are at a sufficient distance from the drilling site.

The main operating plan can be drawn up in such a way that it includes the entire drilling site. The drilling of wellbores to explore for geothermal heat potential would then be generally permitted. However, special operating plans are still be required for individual boreholes under the provisions of § 52 para. 2(2) of the BBergG. In this respect, the procedure can potentially be simplified in that the type and number of the wellbores are so precisely described in the main operating plan that they are thereby already included and approved. In such a case notification then only has to be given that drilling is underway on individual boreholes that have been specifically and precisely described within the scope of the main operating plan. This primarily serves as an indication of how the excavation work is progressing.

Other than that, certain exploration activities, such as individual wells and the measures that accompany them, have to be applied for by way of the appropriate special operating plans. The eligibility for approval as such is fixed under the terms of the main operating plan and it is within the scope of the latter that there is scrutiny of all the relevant points that can stand in the way of the project. These then comprise the elements that have to be checked and tested in relation to the requirement for a general operating plan at this level. It is then necessary, at main operating plan level, to strike a balance between the arguments in favour of the exploration activity and the opposing interests. However, there will be no significant interests opposing the scheme. Consequently, there will be no need to weigh up the facts of the case in anything like the depth provided for by the Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfG) in its Garzweiler ruling (25) on general operating plans for the opencast lignite mine, and for expropriations for this purpose, and for main operating plans, which had to be delivered because no approval had yet been given for a general operating plan.

5 Connection to fracking

A moratorium on fracking has existed in North Rhine-Westphalia for some time. Measures in connection with fracking cannot be approved until such time as the risks associated with this technology have been clarified. Legal reservations already existed in respect of this issue prior to the enactment of the law on fracking on 24th June and 8th July 2016 (26). According to § 13a para. 1 of the Federal Water Resources Act (WHG), geothermal drilling cannot henceforth take place using fracking technology (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. There are legal reservations about the use of fracking technology in Germany because of the potential environmental hazards associated with the fracking fluids. // Bild 4. Gegen die Fracking-Methode bestehen in Deutschland wegen möglicher Umweltgefährdungen durch die dafür verwendeten Flüssigkeiten rechtliche Bedenken. Source/Quelle: ©mojolo – stock.adobe.com

Such operations are only permitted under § 13a para. 4 of the WHG, and then only outside excluded areas using mixtures that are rated as having no more than a low water contamination risk, and deploying the best available techniques. Such an operation cannot then be obstructed by any ordinance issued by the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. No refusal of an authorisation can therefore be derived from this.

However, the general exclusion of fracking also applies to specifically planned deep drilling operations (27). Here the aim is to achieve free flushing using conventional acidification methods. Such operations set out to explore, identify and activate existing fracture structures. Heat exchangers are then installed within these natural rock bodies, the aim being to establish circulation in the extension structures.

Such an arrangement, which also applies to deep drilling, satisfies the decreed North Rhine-Westphalia moratorium and the law on fracking too, both of which hold that unconventional fracking projects are not eligible for approval. The moratorium applied by the State of North Rhine-Westphalia also covers geothermal boreholes greater than 1,000 m in depth, both with and without fracking measures, and for which “it may potentially be possible to transfer the findings obtained here to geothermal wells with frack treatment” (28). The first issue is that this frequently involves a geothermal borehole without fracking measures. The well is aligned in such a way that it uses the extension structures and so gets by without chemical substances. It merely operates using conventional acidification methods. The findings obtained in such cases cannot thereby be transferred to geothermal boreholes with frack treatment. Such a possibility can be excluded from the outset.

The second issue that arises is the question of how this wording is to be understood in the aforementioned ordinance. In systematic terms it is connected with the report referred-to in the heading, which includes a risk study of the exploration and extraction of gas from unconventional deposits in North Rhine-Westphalia and the impact of such operations on the ecosystem, and in particular on public drinking-water supplies. The sentence that is open to question can therefore also be taken to imply that the findings from this report can potentially be transferred to geothermal boreholes with frack treatment. According to this, the exclusion would in any case only apply to geothermal boreholes with frack treatment in which the findings from the aforementioned report take effect. These wellbores would in fact have to be positioned in the same way as fracking practised outside geothermal boreholes, so that the findings in the report can be transferred. From this perspective it would be a completely straightforward process – even in the context of the decree issued by the Ministry for Industry and the Environment of North Rhine-Westphalia – to authorise the drilling of geothermal boreholes greater than 1,000 m in depth without frack measures. This continues to apply even after the adoption of the new law on fracking. In any case none of this poses a general obstacle to geothermal drilling activities (29).

6 Overall conclusions and prospects for repository exploration

Geothermal drilling is largely subject to mining law, this applying both to approval and licensing and to legal liability. While activities carried out on private property, and boreholes drilled for the purpose of teaching and instruction, are essentially excluded from these provisions, test wells are not. However, water legislation requirements continue to apply in this respect and these must be observed at all times. For geothermal wells with frack measures the ban on unconventional fracking takes effect in accordance with the new fracking law. However, this is not applied to wells that do not involve fracking measures. If the requirements under § 21 para. 2 of the Repository Site Selection Act (StandAG) have not been met, the Act does indeed bar the drilling of geothermal wells in those areas that have now been identified where the geological formations are considered suitable for providing the highest possible level of safety. In this respect, and in view of the energy transition process currently under way, an open-minded approval process is now required (30). The Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BfE) has hitherto regularly given its approval for commissioned projects (31). This will largely continue to be necessary as those sub-areas presenting favourable geological conditions under § 13 of the StandAG are still being identified (32).

References/Quellenverzeichnis

References/Quellenverzeichnis

(1) Beschluss des Bundesrates, BR-Drs. 353/16. Veröffentlicht in BGBl. I 2016 S. 1962 und 1972.

(2) Preuße, A.; Weiß, E.-G.; Würtele, M.: In: Frenz, W./Müggenborg, H.-J./Cosack, T./Hennig, B./Schomerus, T.: EEG, 5. Aufl. 2018, vor § 45, Rn. 33.

(3) Zu deren Voraussetzungen im hiesigen Kontext von Marschall, in: Festgabe 200 Jahre OLG Hamm, 2020, S. 364 (372 ff.).

(4) Bereits Greb, K.: Beck Online-Kommentar EEG 2014, 2015, § 48, Rn. 34.

(5) Bergbehörde NRW: Nutzbarmachung geothermischer Energie (Erdwärme) in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Unveröffentlichte Position der Bergbehörde NRW, 2009, S. 1 f.

(6) Vitzthum, S.; Piens, R.: In: Piens, R./Schulte, H-W./Vitzthum, S.: BBergG, 3. Aufl., 2020, § 4, Rn. 12.

(7) OVG Bautzen, 4 B 832/03 v. 10.02.2004.

(8) Piens, R.: In: Piens, R./Schulte, H-W./Vitzthum, S.: BBergG, 3. Aufl., 2020, § 127, Rn. 7.

(9) Piens, R.: In: Piens, R./Schulte, H-W./Vitzthum, S.: BBergG, 3. Aufl., 2020, § 127, Rn. 8.

(10) Böhme, M.: In: Berendes, K./Frenz, W./Müggenborg, H.-J.: WHG, 2. Aufl. 2017, § 49, Rn. 3 a. E.

(11) S. näher BT-Drs. 18/4714 v. 23.04.2015, S. 13 ff. sowie Frenz, W.; Slota, N.: ZNER 2015, 307.

(12) OLG Düsseldorf, Az. 18 U 88/02 v. 18.12.2002; die dagegen gerichtete Revision nahm der BGH, III ZR 31/03 v. 29.04.2004 nicht zur Entscheidung an; ebenso OLG Düsseldorf, I-20 U 4/04 v. 08.06.2004 im Anschluss an BGH, III ZR 234/97 v. 29.07.1999 für Bergschäden.

(13) Bereits Boldt, G.; Weller, H.: BBergG Kommentar 1984, § 114, Rn. 10.

(14) Siehe Spieth, W.-F.; Wolfers, B.: ZfB, 269, 1997.

(15) Knöchel, H.: In: Frenz, W./Preuße, A.: Spätfolgen des Bergbaus, 2000, S. 103 (108).

(16) OLG Düsseldorf, Az. 18 U 88/02 v. 18.12.2002.

(17) RG: ZfB 1898, 228.

(18) OVG Münster, 12 A 2194/82 v. 29.03.1984.

(19) BVerwG, 4 C 25/94 v 09.11.1995 bezogen auf die Nachsorgepflichten.

(20) BVerwG, 4 C 25/94 v 09.11.1995; näher dazu Frenz, W: Ewigkeitslasten im Kohlenbergbau, 2016.

(21) BVerwG, 4 C 25/94 v 09.11.1995.

(22) BVerwG, 7 C 22/12 v. 18.12.2014.

(23) Dazu näher von Marschall, in: Festgabe 200 Jahre OLG Hamm, 2020, S. 364 (378 ff.).

(24) Siehe zu dieser Stufung BVerwG, 7 B 43/09 v. 22.04.2010; Frenz, W.: NVwZ 2011, 86.

(25) BVerfG, 1 BvR 3139/08 u. 1 BvR 3386/08 v. 17.12.2013.

(26) Frenz, W.: NVwZ 2016, 1042.

(27) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit, BT-Drs. 18/8916 v. 22.06.2016.

(28) Ministerien für Wirtschaft und Umwelt des Landes NRW, V B 1-47-03/IV-5-3052-37727 v. 18.11.2011.

(29) Von Marschall, in: Festgabe 200 Jahre OLG Hamm, 2020, S. 364 (383).

(30) Näher Frenz, W.: DVBl 2018, 285.

(31) Von Marschall, in: Festgabe 200 Jahre OLG Hamm, 2020, S. 364 (388).

(32) Zwischenbericht Teilgebiete gemäß § 13 StandAG der Bundesgesellschaft für Endlagerung, SG01101/16-1/2-2019#3 v. 28.09.2020.