Status of the EU coal industry and the EU initiative “Coal Regions in Transition”

The final decision for the coal phase-out taken in Germany in 2020 and justified on the grounds of climate policy neither was nor is a strictly national project; it is rather one element of a European framework. Back in December 2017, the previous EU Commission had launched the “Coal Regions in Transition” initiative in Strasbourg (a part of the implementation of its “Clean Energy for All Citizens” package of measures) with the aim of promoting a structural change away from coal mining and use throughout the EU. (1) The EU, however, cannot simply issue a decree requiring its member states to realise a coal phase-out; it can only provide structural policy support and accelerate its implementation indirectly, above all through European environmental and climate policy framework conditions, because the countries still have authority over the energy mix within their borders in accordance with Art. 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Nevertheless, a coal phase-out is officially classified by the EU Commission as a “progressive European reality” over the course of the decarbonisation strategy initiated by the EU. (2) The initiative explicitly aims to ensure that the regional and social consequences of this development are cushioned and that no coal region of the EU is left behind. Since the proclamation at the end of 2019 by the (new) EU Commission (with the approval of the Council and all European institutions) of the “Green Deal for Europe” and its goal of climate neutrality for the EU by 2050, the coal phase-out has also been viewed as an entry-level and groundbreaking project on this highly ambitious path. This project will be supported by a “Just Transition Fund” endowed with 17.5 Bn € in the current EU budget from 2021 to 2027, but its funds can be increased many times over through other EU programmes (EU Invest, regional and social funds), EIB loans, national measures and private investment. From an energy and regional economic point of view, however, this “coal transition” in the EU poses considerable challenges for which special measures are envisaged (Figure 1).

Fig. 2. Cover Page JRC Study Recent Trends in EU Coal, Peat and Oil Shale Regions. // Bild 2. Titelseite JRC-Studie Recent Trends in EU Coal, Peat and Oil Shale Regions. Source/Quelle: EU-Kommission

In a new estimate presented in spring 2021 (Figure 2), the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the EU Commission still attributed, directly and indirectly, as many as 340,000 jobs in the EU to the coal sector. (3) Coal mining and/or coal-fired electricity generation has been identified in 19 member states and in a total of 94 (NUTS 2) regions in these states. Coal-fired power generation still accounts for about one-fifth of electricity generation in the EU as a whole, even though it has fallen dramatically in recent years (by more than one-third between 2012 and 2020 alone). As of 2018, there were still 90 active coal mines in eleven member states across the EU, providing directly and indirectly almost 210,000 jobs; many of these, however, such as the last two German coal mines, have been closed down since then. In 2020, 166 coal-fired power plants with a total capacity of around 112 GW were still in operation in 18 EU member states. Moreover, coal was used in 25 regions of the EU as a specific raw material in CO2-intensive industries, especially in the steel industry, but sectors such as chemicals, cement and paper also figure prominently. In addition, the Coal Regions in Transition initiative was expanded in 2019 to include the oil shale industry (exclusively in Estonia) and peat mining and power generation (in the Baltic countries, Sweden, Finland and Ireland) with a total of around 19,000 direct and indirect employees as these sectors are also considered unsustainable in the long term from the perspective of climate policy. Depending on the scenario, the JRC expects the permanent loss of between 54,000 and 112,000 of these jobs in the EU by 2030 and the loss of all remaining jobs by 2050 in the course of the planned full decarbonisation.

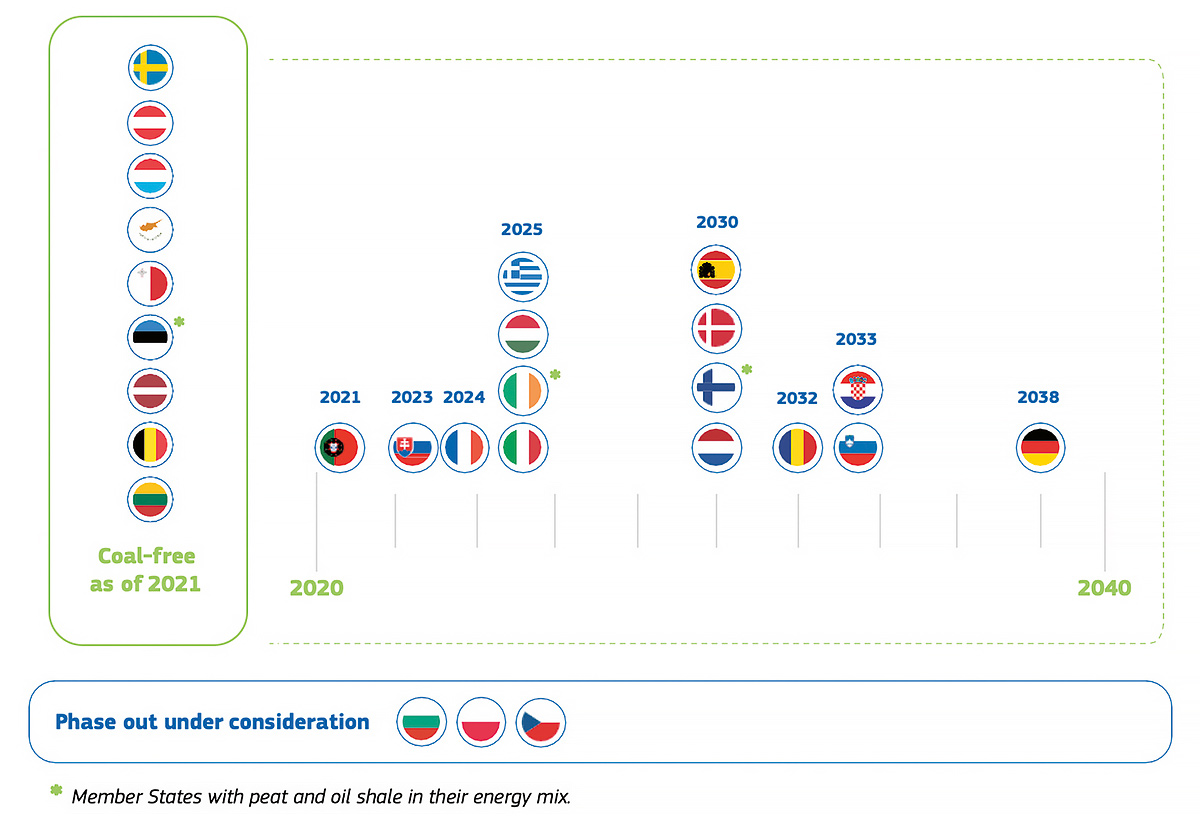

By the end of 2021, no fewer than eight (Western European) member states will be coal-free. Twelve member states, including classic coal countries such as Greece (by 2028), Spain (by 2030) and Germany (by 2038 at the latest), have committed to a coal phase-out as well as a phase-out of oil shale and peat. Three other member states are currently discussing phase-out plans, including the Czech Republic (target year probably 2038, but not yet definite) and even Poland (currently with an end date of 2049). Only three EU countries – Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia – do not yet have a phase-out plan or decision, but their coal industries are also under immense pressure from climate policy targets, especially the sharp rise in CO2 prices in the European Emissions Trading System. This is the setting for the establishment of the Coal Regions in Transition initiative as an open forum inviting all coal regions of the EU to seek assistance for these challenges. On the one hand, it offers an information and dialogue platform organised by the Commission for all stakeholders, i. e. for the affected local, regional and national governments and their pertinent institutions, for affected or involved companies, associations and trade unions, for all non-governmental organisations interested in this field (primarily environmental organisations) and for the scientific community. As of the first half of 2021, there had been a dozen related platform events – in online format only because of the coronavirus pandemic – and various side events. On the other hand, the initiative is expected to provide information on available EU financial assistance and practical support at all times. The latter includes active networking of stakeholders and support for their cross-border cooperation as well as targeted technical assistance in the development of concrete regional transition strategies – partly through on-site advice for so-called start-up regions by EU experts, partly through the provision of supporting resources in the form of materials such as guidelines for funding measures, fact sheets, selected specialist publications and various international case studies on such topics as the InnovationCity Ruhr, other European coal regions or the structural change of the coal regions in the US Appalachians. Especially important in this sense are the guidelines for strategy development officially referred to as “toolkits”. These materials have been prepared in addition to all its organisational tasks by the initiative’s secretariat, which since 2019 has been run by the Commission in collaboration with the consulting organisations Ecorys, Climate Strategies, ICLEI Europe and the German Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy (Figure 3).

The following remarks on the tools of the Coal Transition, which have been developed partly as input and partly as output of the dialogues that have taken place, essentially refer to the five toolkits published by mid-2021. They are intended to show conceptually what strategies could be used by the EU or its coal regions for an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable phase-out of coal. The primary statements of these toolkits and the individual tools for transition they provide are bundled closely together for analysis and assessment from a primarily economic perspective committed to post-mining research. (4)

“Transition Strategies” toolkit

This toolbox has been created primarily to aid regional policy makers and engaged stakeholders to develop and design effective transition strategies for the EU’s coal regions and to identify supporting actions and projects. With this in mind, it presents a number of fundamental ideas and concepts. Moreover, it offers guidance for monitoring and evaluating the strategies and for their continuous adaptation.

It is stated at the outset that there can be no patent strategic solution, no “one size fits all” strategy. The coal regions in the EU differ in their economic structure and culture, their governmental systems and political frameworks and in their financial, infrastructural, geological or know-how-related capacities. There is no alternative to giving due consideration to the specific circumstances of each region and locality, and all actors must go through learning processes (“learning journey”). Nevertheless, there is a general logical cycle of strategy development illustrated by the so-called policy cycle: problem analysis – setting of goals – selection of measures – evaluation and policy adjustment.

The problem analysis and definition roughly sketch the general structure (“framing”) for the orientation of the actions that are desired (“agenda setting”). The question of what the future of today’s miners and coal-fired power plants should look like, e. g., sometimes takes a different direction from that of the economic future of the affected mining region as a whole. Consequently, a detailed discussion of the problems and possible solutions with a broad spectrum of major stakeholders as well as the establishment of participation processes that assure the high quality of the informational basis of the strategies, provide as holistic a picture as possible and create the basis for commitments of the actors during the later implementation are important. Strategic planning must quickly gather key information while simultaneously creating capacities in the region (competences, institutions, cooperative actions) so that it is possible to process relevant data and to make available the knowledge required for future adjustments. Such elements include, e. g., the mining and geographical characteristics of the region, social and demographic factors, the special economic and technical circumstances and the institutional situation.

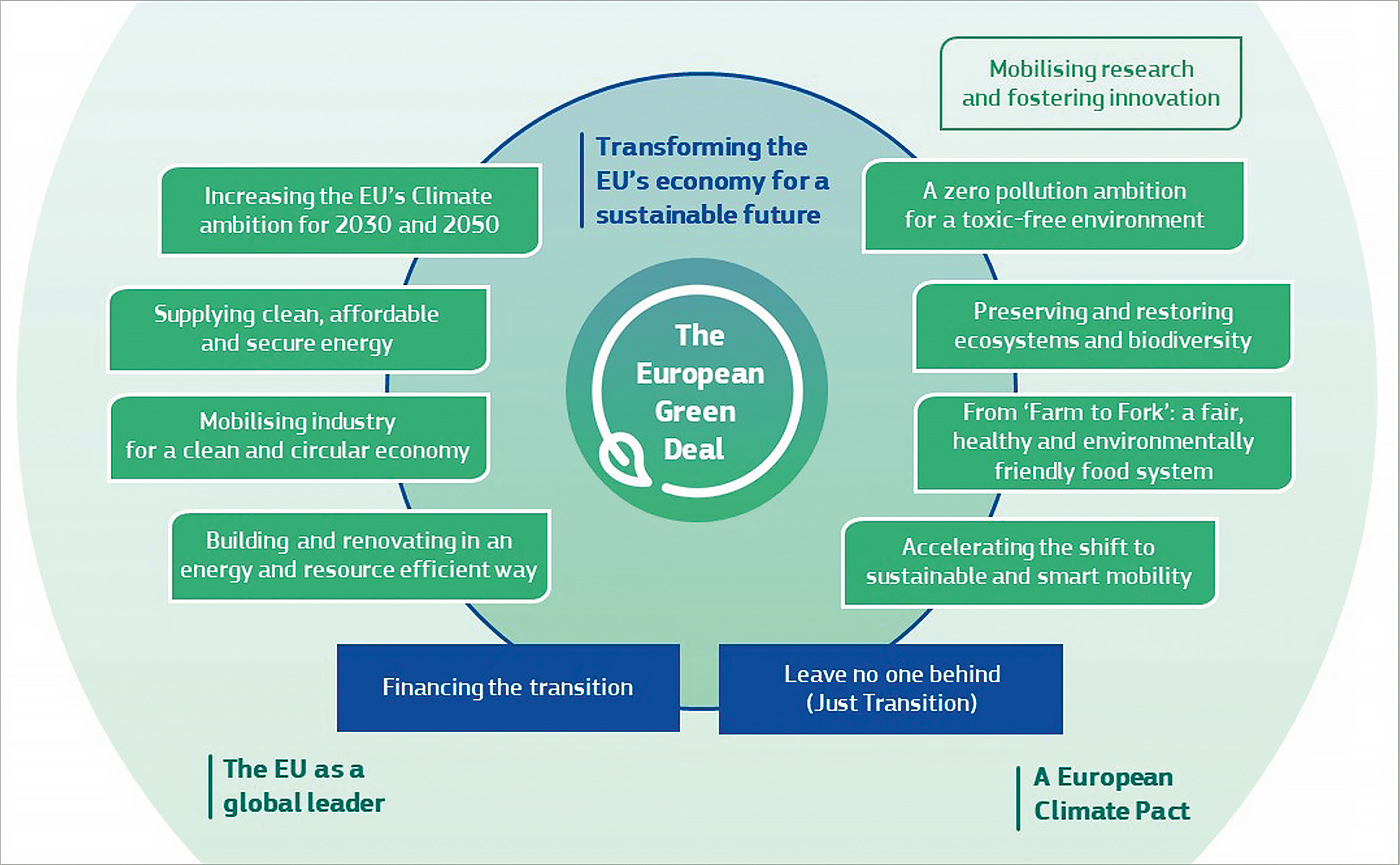

The target definition should include a solid long-term vision for each specific coal region with a time horizon of about 30 years (adequate for structural transformational processes) as well as more concrete and detailed development goals with shorter time horizons, e. g., five to ten years. This should be complemented by political leadership for the intended goals and clear mandates for institutional responsibilities. It is also necessary to harmonise regional goals with overarching international and European objectives. The UN Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Climate Agreement and the EU Green Deal (Figure 4) are highlighted here as are the industrial strategy, the cohesion policy and the EU Clean Energy Package.

At the level of measures, the first step is to identify the main strategic options for action. In addition to the concrete ideas of the people doing the actual work, unconventional ideas (“thinking out of the box”) must also be generated and weighed. For the latter, there are a number of formalised procedures for which experts from advisory or research institutions can provide assistance; reference is also made to manuals from various expert groups. Quantitative and qualitative scenario techniques and related methodological approaches such as so-called backcasting or the theory of change are addressed. In determining the measures to be considered, there are a number of typical challenges and risks that need to be taken into account, brought to mind and, as necessary, discussed at length: conflicts between differing objectives and between short-term concerns and long-term vision, fixed interests, lack of innovation or synergies, limited institutional capacities. In addition to public transparency and broad stakeholder participation, multi-criteria analyses would be particularly helpful in the selection of measures because sensitivities, conflicting goals and power discrepancies can be revealed and balanced more easily. Finally, a key role for regional development measures in the coal regions (although not only here) is played by customised financing strategies that provide access to related financing options. The various EU funds and the new Just Transition mechanism can be mentioned from the European perspective.

Finally, political learning and adaptation processes are indispensable for the optimisation of transition strategies. This requires from the outset planning in cycles that allow for revisions, public debates on the strengths and weaknesses of the paths taken and the willingness of political decision-makers to monitor and evaluate the strategy and to accept its results. The inputs and outputs of the strategy development, the results actually achieved in the realisation and their impacts and contributions to the goals must be evaluated. The integration of a monitoring and evaluation system with related reporting into the policy cycle from the beginning is necessary to achieve this. It should include suitable quantitative (directly measurable) as well as qualitative indicators that reflect the various economic, social and environmental strategy goals, and it should be designed so that it can be incorporated into future decision-making processes.

It goes without saying that such an EU-wide toolkit can provide only very general recommendations for the formulation of transition strategies in view of the tremendous diversity among the European coal regions. One noteworthy aspect, however, is that, on the one hand, the regional level is addressed and, on the other hand, special attention is given to guiding goals on the international and European level. Nevertheless, typical problematic circumstances of coal regions and significant national target systems are not addressed at this time, (5) revealing a certain detachment of the underlying EU perspective from reality. The effort to utilise the trusty methods of rational planning for the Coal Transition and to make them accessible to the coal regions and an (interested) wider public must be acknowledged. Still, the fundamental question arises as to what extent such direct management of structural transformation – as discussed here for coal regions – is at all possible in basically market economy systems such as those essentially found within the EU and whether it is in conformity with regulatory policy. (6) From an economic perspective, it is clear that regional and sectoral structural transformation is generally an evolutionary process that can be steered politically by state planning actors and procedures, however they may be decided, solely to a very limited extent, whether at regional, national or especially European level. They can at best influence but never comprehensively control, much less compel the multifaceted, decentralised decisions – sometimes in competition with one another and often innovative as well – made within a web of complex relationships among private producers and consumers in the (coal) regions, and in a globalised economy the chance of impacting these decisions outside these regions is virtually non-existent. (7)

“Governance of Transition” toolkit

The “Governance of Transition” toolkit is by its nature very closely related to the transition strategies discussed above as its particular objective is the development of governance models that will provide adequate support to transition processes. As defined in this case, “governance” is generally understood as a reference to the established channels through which various influential actors and institutions employ formal and informal means to achieve collective (i. e. politically determined) goals. The structure of the toolkit is aimed specifically at finding effective strategic arrangements for a coal transition within the setting of regional governance. In a sense, governance is always at the heart of the policy cycle outlined above and is involved at every stage. In addition, the structural distribution of power and influence on the decision-making processes depends on the applied governance model.

The competent national, regional and local levels of government, the government agencies in charge of regional development and the civil society organisations engaged in this field, whose participation and involvement are recognised from the outset as playing an important role in successful transformation, are designated as the toolkit’s target groups. The significance of “social dialogue” and “inclusive processes” for the design of transition strategies, which must always take into account a multitude of decision-making levels (“multi-level”) and actors (“multi-actor”), is correspondingly great. In terms of regional policy, solely governance models that incorporate the viewpoints of various actors or their representatives and recognise them as legitimate will ultimately be effective. The involvement of these stakeholders must be grasped as an ongoing process that should start early and that demands leadership and organisation. This must be linked to an active communication strategy that also informs the general public about the workings of the process, how meaningful participation is possible and what will happen next.

The establishment of suitable governance models on the basis of a step-by-step guide is recommended. Before any other action is taken, the existing governance structures, their key actors and their roles and responsibilities and the political balance of power need to be identified and analysed. The next stage is the creation of transparency, the clarification of questions of legitimacy and the ensuring of a broad representation of stakeholders. Responsibilities for key decisions must be clearly delegated and partnerships for the subsequent phases of implementation must be concluded. During this phase, the specific levers of influence and windows of opportunity must be taken into account. Every governance model must evolve over the course of time in response to critical reflection and adaptation and repeatedly weigh anew when what actors must become involved. Several specific institutions from European coal regions are identified, including – with respect to German lignite – the Zukunftsagentur Rheinisches Revier, exemplifying how different levels and actors can work together in practice across various government-administrative levels based on agreements between local governments and civil society or jointly organised by municipalities, business associations and trade unions.

As far as participation of and partnership with non-government stakeholders is concerned, the difficult political task is to find the right balance between information only, advisory role/consultation and active cooperation in decision-making. The toolkit advocates intensive stakeholder participation in all cases. The advantages of this approach would be in the development of trust and legitimacy, the heightening of awareness and acceptance, an increase in the effectiveness and speed of process progress, long-term savings in the use of resources, the broadening of the knowledge base of decision-makers and the stimulation of crucial innovation. Certain typical obstacles and problems of stakeholder engagement are acknowledged. These processes are often time-consuming and consume considerable resources. It is difficult to obtain significant contributions from some groups. It is not uncommon for there to be a lack of agreement on what information is needed for decisions and what all needs to be “taken into account” and in what form. But the failure to involve major stakeholders carries significant risks; a lack of trust and uncertainties about acceptance of results, division into divergent factions and particular groups, perpetuation of “silo thinking”, inefficient use of funds, ethical conflicts and compliance problems. Consequently, the search for a solution to the aforementioned issues focuses on the following governance approaches: long-term commitment to stakeholder participation that continues beyond the decision-making phase in conjunction with clear expectations; active generation of public awareness of the need for decisions, prompting greater willingness of certain stakeholders to become involved or to secure the commitment of those already on board; the targeted support or facilitation of the participation of those voices that are not usually involved in decision-making processes or who have fewer opportunities to join in; and joint evidence and fact-finding processes as a basis for more objective and constructive debates with stakeholders. The toolkit expressly notes several good examples of stakeholder participation in the recent past: the consultation process for the Coal Transformation Action Plan of the Upper Nitra region of Slovakia, which was carried out with strong citizen participation, and the plans for the socially responsible phase-out of coal mining in Spain and of German hard coal in the coalfields of North Rhine-Westphalia and Saarland negotiated between the national and regional governments, mining companies and trade unions (Figure 5).

This toolkit also displays a relatively ideal-typical, even naïve point of view along with a number of elements of general insights and experience for governance processes that do not, however, concern solely regional (coal) transition strategies. In practice, the conduct of political decision-making processes is seldom as systematic, balanced, independent of strong individual interests and significantly based on expertise – issuing from a social vacuum in a bell jar, so to speak – as assumed here. Experience with political disputes and conflicts, which play a major role especially in the topic of governance, has hardly been addressed and has not been analysed in greater detail – regrettably – so practical tools are missing. Another shortcoming: while substantial importance is attributed to stakeholder participation, there are no explicit suggestions for actions that would secure the best possible involvement of the coal companies and their employees, although they are the primary stakeholders in the Coal Transition. Nor is there any discussion of how the fundamental problem of the democratic legitimacy of representatives of groups and organisations vaguely designated as civil society, such as the environmental activists who are de facto especially numerous in the thematic field of the Coal Transition, in comparison to the elected representatives of the people and the office holders they have appointed is to be resolved.

“Environmental Rehabilitation and Repurposing” toolkit

Fig. 6. The 55-m-high double shafthead frame is the landmark of the Zollverein UNESCO World Heritage Site, the city of Essen and the entire Ruhr Valley. // Bild 6. Das 55 m hohe Doppelbock-Fördergerüst ist das Wahrzeichen des UNESCO-Welterbe Zollverein, der Stadt Essen und des gesamten Ruhrgebiets. Photo/Foto: Jochen Tack/Stiftung Zollverein

This toolkit – remarkably illustrated with numerous photos of the German (coal) World Heritage Site Zollverein (Figure 6) and others – explicitly claims to present key ideas and concepts for the ecological rehabilitation and economic repurposing of mining infrastructure that will support governments and institutions in these two tasks. Knowledge and tools are presented, including specific suggestions on how to secure funding.

It begins with the definition of some key terms such as mine closure, mine completion, mine rehabilitation, perpetual obligations (long-term to permanent, under certain circumstances eternal obligations after the end of mining operations) and forms of reuse – the latter explicitly described as socially beneficial reuse of closed mines and other industrial facilities as well as the associated land areas, although the precise meaning of “beneficial” remains vague. Further remarks are preceded by a series of key messages: the rehabilitation and reuse of former mining assets must be viewed by politicians and the public as a significant challenge for coal regions in transition. Their intent is first of all to protect citizens and the environment from ecological damage or to repair any such damage as far as necessary and, at the same time, to attract new economic activities and create new or alternative jobs at the sites in question. In any case, the associated financial risks make government intervention unavoidable. Simultaneously, mine closures offer the opportunity to coordinate the redevelopment and reuse of their locations more closely with public long-term plans and regional development interests. The utilisation of certain tools and good practices aids in the acquisition of the required knowledge and capacities. The prerequisite for successful transitions is intensive coordination leading to accelerated implementation and acceptance by the local population. Pertinent regulatory requirements must also be observed at all times. In Europe, mine closure processes are highly regulated by the government, partly on the basis of general legislation, partly pursuant to licensing procedures specific to the region or location; details vary from member state to member state, sometimes even from mine to mine. The competent authorities must ensure proper compliance with rehabilitation requirements and prevent the burdening of municipalities and their taxpayers with unreasonable costs for environmental measures.

There is specific reference to the importance and possible support from the use of databases for the management of statistics about post-industrial and unused land areas, of a standardised and computerised “management tool” for mine closures such as CLOSUREMATIC (which has been developed under the leadership of the Geological Survey of Finland) and of guidelines for integrated closure planning based on experience such as the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) “Good Practice Guide” published in 2019.

The toolkit also lists typical closure costs – from the costs of planning the closure, demolition of facilities, shaft backfilling, safety measures and mine water management to site rehabilitation and long-term aftercare – and explains the need to secure their financing in advance. Otherwise, it will not be possible to fund the full costs of the environmental rehabilitation and obtain the financial resources necessary for it. The financial risks for all parties involved – companies as well as regions – are reduced. It must also be determined when government intervention would be necessary and no other financing solution would be possible, e. g., in the case of sudden bankruptcy of the mining company. Three tried and tested approaches to solving the financing issue are highlighted: the pooling of various public funds and possibly the obligatory provision of private funds by the mine operators for the rehabilitation of mining legacies – the Australian Mining Rehabilitation Fund is cited as an example – the establishment of a state-supported or directly state-operated run-off company for the rehabilitation tasks and the specifically German model for the financing of the perpetual tasks after the end of the domestic coal industry, namely, the establishment of the RAG-Stiftung, a private-law foundation. The latter created its foundation endowment from the capitalisation of the former “white”, non-mining division of the RAG Group. Curiously, only passing mention is made of the short-term solution, common in Germany at least and not restricted to environmental contamination, of creating provisions during ongoing mining operations that are backed by additional forms of security.

The toolkit explains that transition management must start by asking itself fundamental questions. What is the crucial challenge in terms of rehabilitation and reuse, what is the optimal transition strategy under the given regional and temporal conditions and how can the economic and social shocks of mine closures be strategically addressed? What conditions or even solution concepts could restore the economic attractiveness of the region and initiate developments towards a meaningful new use of the mining areas and their rapid transformation while reducing negative effects such as job losses? What alternative energy sources could replace the lost contribution of coal at similar cost and supply conditions? How can the identification of balanced post-coal uses of the land areas in question be facilitated, whether they are suitable for economic, environmental, recreational, energy-related or open space reserve purposes, e. g., for forests as carbon sinks or other environmental compensation measures? All these issues are precisely the critical questions of the transition to which a toolkit of this type would be expected to propose answers or approaches; instead, it does no more than call for remedies to be found.

In contrast, typical challenges are explicitly mentioned. The potential for reuse is not easy to determine as it depends on a variety of regional and local factors such as the specific geographic conditions of the site, sectoral demand and special economic opportunities etc. The risks depend on the nature of the region and type of former mining as well as the characteristics of the mine sections for which a reuse is sought. The right timing is just as important as the harmonisation with the framework plans already in place. Extraordinary challenges arise when the planned time horizon changes – i. e., in the event of premature or sudden closure of mines or when other planning assumptions become obsolete due to a change of ownership or other such occurrences. A few typical practical problems are also mentioned, yet no concrete approaches, much less recipes for their solution, are offered. Examples include the difficulties of organising local expert teams or cooperation with local businesses; the persistent problem of pursuing continuous and long-term strategies beyond short-term measures; the loss of one of the largest regional employers and “downsizing” of the local employment potential, possibly with further indirect job losses in the secondary economy; the disparities between the wages customary in coal mining and the often lower wages in alternative employment; and the surrender of cultural identities that were associated with the hard labour in mining. The only comment is that the process of decarbonisation and coal phase-out is unstoppable and that opposing it only increases the dimensions of the decline suffered by a coal region. The challenges must be met head-on in any case.

There is also the emphasis, however, that the described challenges are accompanied by significant opportunities; coal regions should regard the unavoidable environmental rehabilitation as a material foundation for a new future and not merely as a burdensome obligation or a legacy that they must somehow wind up. Rehabilitation and reuse also provide substantial economic possibilities for the mitigation of the negative socio-economic consequences of structural change. Rapid and efficient reuse of land and infrastructure is often a decisive factor for new businesses and jobs in the region. At the same time, however, the preservation of the cultural heritage of mining and the dignity of its miners must be considered and classified as extremely important success factors during the transformation. Many coal regions have come to appreciate the legacy of their mining infrastructure and buildings in later phases of transition, sometimes decades after the mines closed.

Finally, the usefulness of new institutions and administrative structures, especially for public management of land development, is described. Incentives targeting the rehabilitation and reuse of mining sites, especially in those countries that do not have a favourable regulatory framework for this, could be offered, or the interests of regional governments and mining companies could be aligned more closely and strategic partnerships among all involved parties could be more easily established, eliminating a shortfall of financing and specialist capacities. The former Grundstücksfonds Ruhr and the Landesentwicklungsgesellschaft North-Rhine Westphalian are mentioned as examples found in Germany, but without, as would have been possible in these cases, taking stock of their longer-term success for the structural transformation of the Ruhr Valley. Surprisingly, the Ruhr Mining Agreement currently in force, which was concluded with the support and signature of the Northrhine-Westphalian state government and is still applied, is not discussed here even though it was specifically presented at the initiative’s platform events.

The assessment of this toolkit determines that its main objective was obviously to create awareness of the pertinent issues for actors with little experience and prior knowledge of the relevant issue and to provide a certain introduction to the contexts. That may be a reasonable goal in itself. From the point of view of people with years of practical experience in the field and experts for the concerns of coal regions, on the other hand, the explanations are relatively superficial and offer almost no new insights. The questions raised far outnumber the clear answers that are given, and answers to the open questions about usable tools are even rarer.

It is difficult to understand why existing expertise in the EU has often been ignored and more challenging problems have been avoided. Germany alone could have been a source of scientific know-how for the relevant topics that could also be used by other (EU) countries, e. g., regarding higher education in post-mining, (8) risk management, (9) mine water flooding (10) or sustainable and at the same time stakeholder-oriented land management. (11)

“Sustainable Employment and Welfare Support” toolkit

This toolkit is dedicated primarily to the transformation of the labour market of the EU’s “coal regions in transition”. It is intended to offer practical guidance on accompanying this transformation so as to provide short-term support to workers from the coal sector and to encourage measures to create new jobs in the coal regions in the medium and long term. There can be no question that the decline in employment in coal mining and in coal-fired power plants will continue and even accelerate in the future. Classic industrial locations, especially those with the types of mono-structures so often found in coal regions, suffer serious economic consequences from the decline of their core industries, and the transition process must give due consideration to the very special behavioural and cultural challenges for the affected people and their communities arising from deeply-rooted traditions in these areas. The specific measures that are required vary as a function of the speed of the coal phase-out. Major topics include qualification and retraining, stakeholder cooperation, financial assistance for (coal) workers threatened with the loss of their jobs and the deliberate economic diversification of coal regions as a means of creating new jobs.

The key messages here are that the transition of the labour market of coal regions is a complex process for which coherence in a number of policy fields is essential, requiring the involvement of the stakeholders and the impacted employees at the earliest possible stage. Employers and trade unions in particular should be actively involved as this is much more effective than isolated government training programmes. Anticipation and planning of the foreseeable change or its focus, magnitude and time horizon are equally vital. Ensuring a just transition means that options that take individual circumstances into account and create short- and long-term perspectives must be opened. Moreover, the financing of the measures must be secured.

On the subject of qualification and retraining, the first proposal is to anticipate future macroeconomic qualification demands (“anticipating skill needs”), which would have to take into account mega-trends such as digitalisation and sustainability. Concrete regional forecasts should be prepared in partnership with key stakeholders. It would be helpful to take stock of the existing skills in the specific workforce (“skill audits”) and match them with the skills in demand outside the coal sector (“skills matching”). The transferability/non-transferability of the available qualifications within the same occupational field, the same sector, the same region or in neighbouring fields of employment should then be examined. The aforementioned examples point to the possibility of coal miners finding new employment in other mining sectors (copper mining, for instance), an industrial technician from a coal-fired power plant moving to a wind farm or a geologist taking a position in a research institute or as a museum director. Whatever may happen, labour market supply and demand must be more closely linked by stimulating investments from other sectors in the coal region, creating new jobs by encouraging entrepreneurship and business start-ups and by connecting local labour markets with the much broader employment opportunities in the region or even beyond.

As far as stakeholder cooperation for the creation of employment alternatives is concerned, the toolkit begins by addressing all actors and organisations involved in labour market issues, from social partners to competent government agencies and financial institutions – including funds managed by the EU Commission – to specialised providers of job training and counselling services. It is important to identify critical stakeholders with an adequate level of commitment – first and foremost the social partners – and to contact them in good time, to enter into dialogue with them for the development of roles and tasks and to create with them a common vision and a mix of actions with a defined timeline in an organised process featuring meetings and workshops. The development of indicators for monitoring is also needed.

A reasonable level of support for the employees affected by restructuring plans presupposes that they or their representatives, e. g., works councils, are provided with information and counselling at an early stage and are engaged in a mutual dialogue characterised by appreciation and trust. Restructuring plans should, if possible, be drawn up jointly by the social partners. It should be noted that the affected workers will find themselves confronted with existential questions such as finding alternative employment, bridging the period until retirement or paying for living expenses during the adjustment process. Support ranging from transfers to/training for another job within the same company, preparatory qualifications or on-the-job training for new employers and regional transfer programmes for parts of the workforce to practical and financial assistance packages for taking up new employment outside the region should be as tailored as possible and based on intensive counselling. There are special needs of three problem groups that will in part require additional welfare support. Early retirement options or assistance bridging the time until retirement could be considered for older (coal) workers. If necessary, they must be granted adequate forms of support for health impairments or, if pensions or pension substitute benefits are not yet possible, special retraining measures. Assistance for younger workers and possibly vocational trainees who lack the necessary qualifications in the form of education and training measures as well as support for the acquisition of practical vocational experience must be organised. Moreover, active assistance in finding a job or payments to cover travel expenses, e. g., might be appropriate for them. It is especially difficult to find new jobs for people who have been unemployed for a long time in coal regions. All types of practical help – from help in preparing job applications to specific training and qualification measures – must be considered. The toolkit proposes as a general recommendation measures for workers from the coal sector that will close skills gaps in the field of digital technologies; this will become increasingly important in all regions and sectors in the future, especially in Industry 4.0.

The toolkit cites the phase-out of German hard coal, which was carried out gradually over a longer period of time with the constructive participation of the miners’ union IG BCE, as a case study of good practice for a socially acceptable reduction of employment. A broad spectrum of the personnel policy instruments used, from early retirement schemes for miners to various qualification measures and offers of new employment opportunities, e. g., the placement of 100 former miners among the staff of Dortmund Airport, is roughly described alongside a number of accompanying measures and developments. Activities of this nature enabled the mining company Ruhrkohle AG (now RAG) to reduce the number of its mining employees from more than 180,000 to fewer than 10,000 between 1969 and 2015 without any employment terminations for operational reasons and redundancies leading to unemployment during this time. Although the period of time that was required is explicitly mentioned, the fact that more than four decades were indeed necessary for this achievement is ignored; a period of time of this length will not be available for the imminent transition processes on the road to climate neutrality – and not only in the coal regions. The completion of the coal phase-out in the EU has now become a matter of greater urgency.

Fig. 7. Cover Page JRC Report Clean Energy Technology for Coal Regions. // Bild 7. Titelseite JRC Report Clean Energy Technology for Coal Regions. Source/Quelle: EU-Kommission

In depicting the creation of alternative employment through economic diversification and transformation, the toolkit first focuses on new jobs in the renewable energy and energy efficiency sectors. According to JRC calculations, “clean energy technologies” could create around 315,000 new jobs in the EU’s coal regions by 2030 and as many as 460,000 by 2050 (Figure 7). This would exceed overall job losses in the coal sector, (12) but does not guarantee full compensation in every former mining community. New employment in some regions would also have to be generated in other sectors, i. e. potentially from the entire economic spectrum beyond the energy sector – essentially a platitude.

According to the toolkit, however, the principle of climate neutrality should guide the transformation. Coal regions in particular should use the inevitable transition as a catalyst for innovation processes. In this sense, coal-related infrastructure and its industrial heritage could be an asset for the future that illustrates the transformation required by climate policy in a special way. In any case, future-proof private investments and state support programmes that are in line with the EU’s Green Deal as well as international competitiveness are necessary. Promoting entrepreneurship, start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises could also serve as a significant means of diversifying the economic base in coal regions.

Some of the elements in this toolkit, just as in the others, barely skim the surface of the issues and sometimes seem arbitrary. The lack of any answers for resolution of the tangible difficulties of creating new jobs is particularly frustrating. Claims that large numbers of new jobs will be created in the renewable energy sector, e. g., always remain focused on the investment and expansion phase. In contrast to the relatively employment-intensive coal mining industry, the level of employment will fall significantly during the operating phase of the plants when (net) new construction has ceased and only replacement and maintenance work is required. Possible conflicts between EU climate goals and international competitiveness are not even briefly addressed. As was also true of the previous toolkits, it is surprising to see such sweeping assumptions that structural transformation can be planned – in this case in terms of the labour market in coal regions – that none of the problems obvious even today are acknowledged and that no lessons are drawn from the more advanced planning of coal phase-out in Germany, either with regard to the regional economic consequences (13) or to the possibilities for employment stimuli for coal regions. (14)

“Technology Options” toolkit

The point of this toolkit is to identify technological means of putting the industry in coal regions on a carbon-neutral path. It presents some of the technology options available today along with technological developments likely in the future that, in conjunction with coal-related infrastructure, could result in the development of new business models in coal regions. Yet interest here is in the facilities and alternatives to coal use, not in the infrastructure linked to coal mining. Explicitly addressed topics concern possibilities for repurposing coal-fired power plant infrastructure, decarbonisation of coal-intensive industries – focusing on the steel industry – the role of hydrogen production for regional development and certain possibilities for non-energy coal use. At the heart of the discussion is the question of what elements of the existing coal infrastructure can be meaningfully integrated into the energy transition and what parts of the regional industrial value chains can be maintained if the EU’s long-term goal of a zero-carbon economy by 2050 is to be achieved.

Three options are presented for the reuse of coal-fired power plants that would prevent these power plants from having to be fully written off as means of production and operating assets in the event of premature closure (“stranded assets”): use as energy storage, conversion to natural gas or renewable energies and non-energy uses. The first two options would have the advantage that the existing infrastructure, or at least parts of it, could continue to be used in much the same way as now and the costs associated with the closure of coal capacities could be reduced. Retraining programmes would give former coal workers the skills required to keep their employment. And the regional identity as an electricity or energy region could be maintained, which could improve public acceptance.

Thermal energy storage, pumped-storage hydroelectric concepts and chemical energy storage units in the form of battery systems are the principal candidates in storage technology. Coal-fired power plants could be converted into heat storage facilities using molten salt for thermal energy storage, which is relevant for both electricity and heat supply; the method is currently being tested in the Aboña I project in Asturias/Spain and is a market-ready technology that can be fitted into existing power plant infrastructure at relatively low cost, albeit with limited capacity and efficiency. So-called Carnot batteries and, as an alternative to molten salt as a storage medium, new types of material mixtures (“miscibility gaps”), in particular various metal alloys, are still the subject of research and development. In contrast, pumped-storage hydroelectric concepts are also based on a technology that is already established on the market, and they offer larger capacities with longer storage times; they use, however, opencast pit and underground mines rather than closed power plants. Moreover, special geographical conditions are required and environmental impacts must be taken into account, factors that seriously restrict applicability as an independently viable business model; in Germany, i. e., there is no ongoing support from the Renewable Energies Act (EEG), unlike the situation for direct hydroelectricity and other renewable energies. Despite various in-depth studies, there is currently not even a demonstration project of this kind in the EU, which is why the toolkit cites the 250-MW hydroelectric project under construction in a closed gold mine in Kidson/Australia, which is planned for 2022, as the only practical example. The conversion of coal-fired power plants to natural gas or biomass power plants – the latter for co-use as well – on the other hand, which is technologically simpler and can be realised in the short term for emission reduction, would be especially feasible; these plants would have a high degree of flexibility, i. e. can be ramped up and down as needed, and would create replacement jobs at the sites. The toolkit nevertheless warns of the “lock-in” risk as both of the aforementioned power plant types could soon also become stranded assets in the EU. The more restrictive climate policy resulting from the Green Deal can be expected to force a systematic reduction of the even now considerable natural gas share in the EU’s energy and electricity mix for energy and climate policy reasons that would begin around 2030 and set a goal of zero for the year 2050. Moreover, the issue of methane leakage during production and transport renders the true climate advantage of natural gas over coal questionable. The use of biomass, on the other hand, has problems because of the relatively low energy efficiency, ecological limits in view of the additional consumption of land and water, environmental conflicts with biodiversity and climate neutrality and – yet another question – whether it is even possible to develop adequate sources of local biomass. With only a few exceptions, using biomass for power generation would not be a sustainable alternative for most coal regions, In contrast, there is an explicit recommendation to combine former coal-fired power plant sites plus innovative storage concepts with other renewable energy sources, be it wind power and photovoltaic plants, be it solar thermal or geothermal plants, depending on the site-specific conditions. e. g., coal-fired power plants could be converted into clean energy hubs where energy production, storage and processing (e. g., into hydrogen) appropriate to demand could be brought together. The Green Hydrogen Hub at the site of the Vattenfall coal-fired power plant in Hamburg-Moorburg that was closed in 2020 after only five years of operation is cited as a prime example of such an opportunity that incorporates hydrogen technology as well, even though it is far from being realised. Finally, a number of non-energy uses for former coal-fired power plants, for which there are practical examples ranging from office space and cultural or educational facilities to industrial parks or data centres and logistics stations for off-shore wind power plants in some EU member states, are also listed.

Meanwhile, the European Green Deal does not stop with the complete decarbonisation of the energy sector, while prioritising the phase-out of coal. The following stages call for the decarbonisation of all sectors, including industry, which accounts for around 25 percent of EU-wide climate gas emissions, and of energy-intensive industries in particular. This will in turn have a significant impact on coal regions, where there is often a relatively large proportion of energy-intensive industries employing a workforce that often exceeds the number of jobs in the coal sector. So these regions are facing a “double transformation”, so to speak. Graphically, there is also a remarkably large regional coincidence in the number of employees in energy-intensive industries and in the mining sector (not only coal).

The crucial challenge here will be the typically long investment cycles (30 to 50 years and more) in many energy-intensive industries, which, with a view to the Green Deal target year of 2050, would require fairly rapid action in terms of climate policy for the launch of new climate-neutral technologies and production processes. Regrettably, the necessary CO2-free technologies are still mainly in the development phase and are mostly economically immature, i. e. not yet competitive in terms of costs. Although energy-intensive companies have often already drawn up their own road maps for their possible paths to climate neutrality, they need political backing as assistance. The economic opportunities for the companies are found in innovative products (“green steel”, “green cement” etc.) with long-term competitiveness while the regions must look to high investments and the preservation of industrial jobs – from which the coal regions could also profit.

The toolkit singles out the steel industry as a representative of the EU’s energy-intensive industries because crude steel production is currently still fundamentally based on coking coal and coke, making it the largest industrial coal consumer today. The steel industry has three technological options for decarbonisation. One such option is carbon capture and storage (CCS) for the waste gases from the blast furnaces, but this procedure cannot completely eliminate CO2 emissions, being limited to the avoidance of direct emissions into the atmosphere at relatively high abatement costs. Moreover, in some EU member states such as Germany, underground CO2 storage still faces very high political and legal hurdles, and the number of potential storage sites that are geologically suitable is limited. These limitations restrict the usefulness of CCS to little more than that of a bridging technology. Alkaline iron electrolysis – so-called electrowinning – is still in the early stages of development; in the long term, it could prove to be the most energy-efficient abatement process for steel, leading to climate neutrality based on green electricity. A consortium led by Arcelor Mittal is currently building a pilot plant for this technology in France. From today’s perspective, however, a competitive contribution is not expected before 2050 and only in the last stages of the necessary transformation of the steel industry. As it stands at this moment, direct reduction based on hydrogen in combination with smelting processes in electric arc furnaces is regarded as the ideal path to climate-friendly steel production as it could reach maturity as early as the 2030s and offer lower abatement costs in the long term. This approach is also a good fit with the hydrogen strategy for industrial transformation now being pursued in many member states and at EU level.

The toolkit foresees a highly significant role for hydrogen in the future energy system, even if relatively high production costs mean it remains limited to applications where direct electrification is not a viable option. It should be noted that hydrogen is in itself not a fuel like coal, crude oil or natural gas, but a produced energy carrier or raw material that is suitable mainly for the storage, transport and distribution of energy. Future primary applications for hydrogen would not be limited to sustainable energy supply for energy-intensive industries, but would also include its use as a raw material for the chemical and refinery industries and in fuel cell technology for heavy goods transport. The extent of climate neutrality would depend on the use of solely renewable sources for the generation of the power required for electrolysis. The EU hydrogen strategy is broadly sketched in its “Road Map to 2050”, which aims for the gradual expansion of hydrogen capacities using renewable electrolysers and other associated infrastructure as well as the creation and regulation of a liquid hydrogen market with an ever-growing number of applications. By pursuing this strategy, the EU even seeks to become the world market leader in hydrogen and to establish the euro as the reserve currency. Hot spots for demand are expected to appear especially in densely populated areas and regions of energy-intensive industry. The intra-European “green” hydrogen supply will be joined by imports from third countries to concentrate on regions with high potential for renewable energies. This is the force field in which the pertinent EU regions, including the coal regions, will have to develop their own regional hydrogen strategies so that they are able to exploit the related opportunities for business and development.

Last, but not least, the toolkit takes a brief look at other non-energy use options for coal as a raw material. Mention is made of carbon fibre and carbon electrodes as well as carbon-based nanomaterials and the use of lignite as a fertiliser surrogate in agriculture. No mention is made here of products such as the crude montan waxes produced from lignite by the German company Romonta. Although there is a certain demand potential for these options in niche markets, there is a considerable need for development in some cases and hardly any genuine prospects for a future-oriented scaling observing the future conditio sine qua non of climate neutrality. The consequence is that these types of technologies would not offer sufficiently resilient opportunities for the future of the EU’s coal regions.

Overall, it must be noted that the discussion of technology options for coal regions in this toolkit has some surprising blind spots. It must be pointed out, e. g., that the much-discussed hydrogen strategy, which is associated with tremendous hopes and expectations, can also be associated with risks, even apart from the virtual absence of any infrastructure; its international competitiveness is still virtually nil and it will not be viable without enormous subsidisation as long as a significant part of the rest of the world does not follow suit as users and suppliers of hydrogen. Nor has it been clarified throughout the EU whether and, if so, for how long, “blue” or “grey” hydrogen based on natural gas or, as in the past, mixed conventional electricity will remain permissible alongside green hydrogen during a transition phase. (15) It is also difficult to estimate the speed and extent of displacement and dislocation effects in the traditional industrial structure if the desired hydrogen breakthrough proves to be a success. The coal regions should also keep this in mind. Moreover, it is incomprehensible that CCS is discussed as an option for steel production, but not for coal-fired power generation – something that the International Energy Agency (IEA), e. g., sees quite differently. (16) The same applies to CCUS technologies (carbon capture, utilisation and storage) aimed at the commercial use of CO2 as a valuable material and that are increasingly finding new applications in plastics production and other areas of the chemical industry, e. g., in addition to the widely known carbonic acid. (17) The possibilities of CO2 reduction in coal-fired power generation from further improvements in efficiency – long referred to as clean coal or HELE technologies (HELE: high efficiency, low emissions (18)) – are no longer even addressed. This is all the less understandable since the toolkit itself, in referring to the methane leakage problem, calls into question the climate advantage of natural gas-fired power over coal-fired power; in this sense, coal would be no less of an option than natural gas, at least as a bridging technology, into the renewable electricity age, especially since at least some EU member states will continue operating coal-fired power plants for the foreseeable future. In principle, the sole issue revolves around the useful lives of existing coal-fired power plants, and the European Commission has just prepared its own methane strategy focusing on methane reduction in oil and gas. (19) It should be added that the specific CO2 advantage of natural gas in power generation can also be negated if the fluctuating operation of natural gas turbines necessary under the conditions of the energy transition and other factors are also taken into account and compared with the flexibility achieved today by hard coal-fired power plants. (20)

Furthermore, it is incomprehensible that the toolkit on technology options addresses solely technologies relating to the use of coal while not losing a word on coal mining. The use of mine gas, e. g., from active or even closed coal mines to generate electricity and as a heat source is ignored. To be sure, the potential here is also limited, but a specific and systematic use of mine gas unquestionably offers energy and climate policy advantages compared to a partly uncontrollable diffusion of unused mine gas. This is precisely why mine gas has so far been included in the EEG subsidies in Germany and placed on an equal footing with renewable energies. In its previously mentioned new methane strategy, the EU Commission has already indicated that it will recommend encouraging the use of mine gas in its implementation directive.

This toolkit on technology options also ignores the option of using gravitational energy in mine shafts (“gravity storage”) although this possibility was presented in detail at one of the platform events of the Coal Regions in Transition initiative at the invitation of the Commission. (21) The same is true of the considerable possibilities of heat generation from mine water, a manifestation of deep geothermal energy that could be exploited to transform closed coal mines into a “heat mine”, so to speak. The Fraunhofer Institute for Energy Infrastructures and Geothermal Energy (IEG) has been conducting more intensive research into these prospects in Germany for some time and has supported its work with related projects in the hard coal and lignite mining regions. Although Great Britain is no longer a member of the EU, it has extraordinary experience in the “coal transition” and has long since determined the enormous potential in “heat from old mines”, i. e. for a district heating supply based on mine water heat from closed coal mines – the Coal Authority approved a regional concept for the first time in 2020, and further tests are in progress. (22)

Conclusion and outlook

Fig. 8. The collection of tools for the coal transition was compiled with the toolkits by the Secretariat of the Coal Regions in Europe. // Bild 8. Der Werkzeugkasten für die coal transition wurde vom Sekretariat der Initiative für die Kohleregionen in Europa mit den Toolkits zusammengestellt. Source/Quelle: EU-Kommission

The collection of tools for the coal transition, compiled at the request of the EU Commission by the Secretariat of the Coal Regions in Europe initiative in the toolkits (Figure 8), certainly contains a number of valuable aids for dealing with the ongoing and still pending structural transformation away from coal. Yet it frequently raises more questions than it provides reliable answers, contributes at times to illusions of plannability and feasibility and, incomprehensibly, ignores some clearly viable technology options. It has become clear that although the Commission and its agencies are giving serious thought to their recommendations for the coal regions and the future of these regions, have joined the other EU institutions to provide support and are listening to the counsel from several sides, they have so far made little use of the expertise that is to be found in the coal industry and in the coal regions themselves. Sometimes the high cruising altitude in Brussels means that things are overlooked. Some decision-makers may also be following the adage that it is better not to ask the frogs whether the swamp should be drained. This attitude, however, makes it very difficult not to leave behind some of the parties affected by the action and to consider all the facts that are important for the region. One must also acknowledge, however, that with the knowledge available today even taking a closer look and staying in closer touch with reality do not assure accurate prediction of many new developments. These uncertainties mean that it is not possible in advance to manage and account for structurally all the positive and negative socio-economic changes that such a far-reaching and fundamental transformation as the politically desired climate neutrality will bring. A further consequence is that, despite all the efforts being made, the future of the EU’s coal regions – and by no means of these regions only – is more uncertain than the politicians would have us believe.

One positive aspect, and one that appears completely reasonable, is that the EU initiative Coal Regions in Transition has been designed from the outset for the longer term and, as the toolkits also make clear, as a project for the decades; the factor of time has been recognised as a major parameter. It is clear – or should be clear – that the transition will not end anywhere with the coal phase-out; regional structural transformation will continue long after – indeed, in some cases will not even begin until then – and will not have been completed generally in 2050. The learning and adaptation processes inherent in governance systems and born from experience, the “learning journey”, can and will take place. It would be good to see the toolkits as well as the dialogue platforms at EU level in the future focusing more on actual experience, examining problems and difficulties as well as success stories and being accompanied more objectively by experts than has been the case to date instead of concentrating on the unconditional fulfilment of the “Coal Phase-Out Mission”.

References/Quellenverzeichnis

References/Quellenverzeichnis

References

(1) See the EU Commission’s official presentation of the initiative: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/EU-coal-regions/coal-regions-transition_en

(2) Ibid.

(3) JRC Science Policy Report: Recent Trends in EU Coal, Peat and Oil Shale Regions, Brussels 2021.

(4) All these toolkits along with other “resources” are available from the secretariat at: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/EU-coal-regions/resources_categories_en?redir=1

The following summary descriptions are based on these publications.

(5) The coal phase-out in Germany does not by any means follow the EU initiative Coal Regions in Transition or direct international statutes, but is based instead on national decisions that, pursuant to the coalition agreement of the German government concluded in 2018, are manifested in the national Act for the Cessation of Coal-Fired Power Generation passed in 2020, the Act for the Structural Strengthening of Coal Regions and related national directives and agreements. Activities are also primarily funded by allocations in national budgets, and EU funds are used to support the structural measures only to a lesser degree.

(6) Cf. Nienhaus, V.: Strukturpolitik. In: Vahlens Kompendium der Wirtschaftstheorie und Wirtschaftspolitik, Vol. 2, 8th Edition, Munich 2003, pp. 443 et seqq., esp. 470 – 471, 478 et seqq., and others for a more critical view of such approaches.

(7) For the market and competition theory foundation of structural transformation processes, cf. van de Loo, K.: Marktstruktur und Wettbewerbsbeschränkung, Frankfurt a.M. et al. 1992, esp. pp. 95 et seqq.

(8) Cf. the anthology of the Research Centre of Post-Mining of the TH Georg Agricola University: Done for good. Challenges in Post-Mining. Ed. J. Kretschmann/C. Melchers, Bochum 2016, here esp. the contribution M. Hegemann/P. Goerke-Mallet: Support of Solving the Problems of Abandoned Mining Areas in Germany by Approvement of University Education, pp. 19 – 32.

(9) Ibid. pp. 33 – 46, the contribution of J. Kretschmann/M. Hegemann: New Chances for Old Shafts – Risk Management in Abandoned Mine Sites in Germany.

(10) Ibid. pp. 146 – 152, the contribution of C. Melchers/T. Dogan: Study on Mine Water Flooding That Occurred in Hard-Coal Mining Areas in Germany and Europe.

(11) Ibid. pp. 153 – 162, the contribution of J. Kretschmann: Stakeholder Orientated Sustainable Land Management: The Ruhr Area as a Role Model for Urban Areas.

(12) Available at: JRC Publications Repository – Clean Energy Technologies in Coal Regions (europa.eu).

(13) van de Loo, K.: The Coal Exit – a High-Risk Adventure for the Energy Sector and Regional Economy In: Mining Report Glückauf 155 (2019) Issue 2, pp. 178 – 193.

(14) van de Loo, K.; Tiganj, J.: Employment Stimulus for Post-Coal Mining Regions In: Mining Report Glückauf 157 (2021), Issue 1, pp. 22 – 40, and IW study on the prospects for German lignite regions by K.-H. Röhl/R. Hentze: Vorfahrt für Bildung und Investitionen, IW Cologne 2020.

(15) Russwurm, S.: Klimapolitik braucht Verlässlichkeit. In: Handelsblatt of 27/05/2021.

(16) Cf. as an example www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions or www.iea.org/fuels-and-technologies/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage; it also contains information about the CCUS pilot project at the Canadian coal-fired power plant Boundary Dam.

(17) Cf. as an example the CO2-based innovative product developments at the chemical company Covestro: www.covestro.com/de/sustainability/lighthouse-projects/co2-dreams or the status of current research on this subject with numerous industrial project partners at RWTH Aachen University: www.ltt.rwth-aachen.de/cms/LTT/Forschung/Forschung-am-LTT/Modellierung-und-Design-molekularer-Syst/Abgeschlossene-Projekte/~kpty/Verwertung-von-CO2-als-Kohlenstoff-Baust/

(18) For current clean coal or HELE technologies (including CCUS), cf. World Coal Institute: www.worldcoal.org/clean-coal-technologies/clean-coal. Cf. the EU Commission Communication of 14/10/2020: “Grüner Deal: Kommission legt Strategie vor, um Methanemissionen zu senken” and the related Commission document eu_methane_strategy.pdf (europa.eu)

(19) For more details, see the Deloitte study on the flexibility of hard coal-fired power plants commissioned by the VDKi, cf. www.kohlenimporteure.de/publikationen/deloitte-studie.html.

(20) Cf. the pioneering company Gravitricity’s own presentation at Home – Gravitricity Renewable Energy Storage as well as reports on this gravity storage concept such as the one from spring 2021 on the successful demonstration project in Edinburgh: www.nsenergybusiness.com/news/company-news/gravitricity-demonstration-project or in a German-language medium: www.cleanthinking.de/gravitricity-entwickelt-schwerkraft–speicher-zum-schnellen-und-flexiblen-netzausgleich/

(21) For information on heat mining, see in particular the work of the new Fraunhofer Centre for Geothermal Energy at www.ieg.fraunhofer.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/ Startschuss für die Fraunhofer-Einrichtung für Energieinfrastrukturen und Geothermie IEG and its short information film “Vom Kohle- zum Wärmebergbau” presented in spring 2021 or the article by R. Bracke in the MRG April issue, abridged version available at https://mining-report.de/english/thermal-energy-transition-with-geothermal-energy-from-coal-mining-to-heat-mining/

(22) Cf. the British government’s notification in February 2020 of the Coal Authority’s approval of the first British district heating scheme using mine water energy in Durham: UK’s first district heating scheme using mine water energy now in development – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk); “updates” and further projects of this type are in the test phase: www.cnbc.com/2021/05/13/former-coal-mines-could-be-converted-into-a-geothermal-energy-facility.html.