Introduction

In 1994, Elkington (2018) coined a phrase “Triple Bottom Line” which refers to a business approach that covers financial, environmental and social aspects of businesses. Triple Bottom Line is also commonly referred to as Profit, Planet and People (Lonmin Platinum, 2012) and is used in the context of sustainability in the mining industry in South Africa. In this country, the first stage of leadership challenges in mining started more than a century ago, bringing into focus profit and shareholder wealth. During the second half of the previous century, the second stage of leadership challenges meant more care for the planet and ecosystem health. In the third stage, towards the end of the previous century, leaders were pushed to develop and demonstrate values with the main aim of addressing the implications of their actions for society as a whole, which is known as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

To meet these leadership demands, mining companies embraced a variety of leadership development programmes, all of which were based on current leadership theories mostly developed and postulated in the previous century. The earliest leadership descriptions underscore the understanding of leadership as a stable series of combinations of personal attributes – specifically that leadership was therefore intrinsic to an individual’s genetic make-up and thus leaders are born and not made, as explained by the Great Man Theories of the 1840s (Scouller, 2011).

With the advent of the use of psychometrics to measure personality and behaviour, leadership theories expanded beyond the “leaders are born” notion and the Trait Theories (1930s to 1940s), which asserted that some people inherit certain qualities and traits that make them better suited to leadership than other people. These theories assumed that intrinsic qualities – such as intelligence, a sense of duty and responsibility, extraversion, creativity, confidence and even values – define, in a composite manner, the traits of a leader. Matthews, Deary and Whiteman (2003: 3) cite American psychologist Gordon Allport who “… identified almost 18,000 English personality-relevant terms …”, clearly implying that there is vast array of personality descriptors, which is most likely to cause confusion. In addition, the main criticism against the Trait Theories is simply that there are large numbers of people who possess these traits associated with leadership, yet not everyone possessing these qualities seeks out such positions or aspires to these levels of leadership.

Psychology as a science, and research within the subject, has given rise to more sophisticated psychometrics, especially with statistical methods incorporating factor analyses that would enable more accurate pinpointing of critical leadership variables in people. Through these measurements the Behavioural Theories (1940s to 1950s) of leadership emerged. These stipulated that leaders are made, not born. This approach was diametrically opposed to the theories of the 1800s. Behaviour theory focuses on the actions of successful leaders, not on their mental qualities or internal states, and led to the rise of behaviourism which asserts that people can be trained (“conditioned” in behavioural terms) to become leaders. The post-World War II years saw the emergence of Contingency Theories (1960s) and Situational Theories (1970s). Contingency Theories of leadership suggest that a particular leader and leadership style are adopted as being the most appropriate or most likely to achieve the most successful outcome, given the specific variables in a particular environment.

Situational Theories merely expand the Contingency Theories to encompass the specific appropriateness of the various styles to a particular situation, e. g., Authoritarian (e. g. in a crisis) versus Participative (e. g. in a team context). These theories are based on the assumption of behaviour control: leaders can change their behaviour at will to meet different circumstances. However, in practice, many leaders find this hard to do. Even after lengthy and intense training, leaders fall back on old behaviours, since unconscious and fixed beliefs, fears or ingrained habits really dictate behaviour (Scouller, 2011). The main challenge here is that the old habits are not unlearned.

Transformational Theories (1980s), also known as Relationship Theories, emerged as human rights movements formed globally during the times leading up to the fall of communism (Edwards, 2010). These focus mainly on the interactions between leaders and followers, with the main component being trust, by which increased levels of motivation are gained from followers; this enables them to inspire people by helping group members see the importance and meaning of the task at hand. These leaders are focused people who are fulfilling their potential, but also, through the performance of the group, accomplish the required task at hand (Smit et al., 2013).

Relevance of the leadership theories and leadership models for the future

Although these theories have contributed immensely to the understanding and development of leadership (and have been applied for a long time), they have also led to conventional thinking about leadership in a conventional world mind-set. This situation is confirmed by the 2017 Project Charter: Human Factors of the South African Mining Extraction, Research, Development and Innovation (SAMERDI, 2017: 3, 4). This states: “The South African mining landscape is littered with examples of failure of new technology implementation. The reasons for these failures have in the main been due to human factors rather than failure of the technology itself”. It also states that “Many of these issues are legacy issues, which are derived from a history of ‘management knows best’, and a fear of involvement of organised labour in discussions, or designs that ultimately affect them more than anyone else.”

“Management knows best” refers to the current frame of reference with regard to leadership. Leadership in mining in the South African context has created a culture that is slow to change and slow to respond in doing things differently. These comfort zones, and the apparent inability of leadership in the mining industry to make a paradigm shift, are hampering what we believe is the required future leadership model for mining.

The mining industry of the 21st century requires a new kind of leader, because the business of mining is the business of people. The extractive activities merely represent the playing field of practising this “people business”. How the extraction and work is going to be done in ten to twenty years’ time will be radically different from current mining practices. Concomitantly, the changing situation of leadership for the future needs to be addressed now (Schultz et al., 2014).

The current leadership theories are mostly two-dimensional, namely work and people. A possible third dimension, such as a specific situation, can be added. Yet all the current leadership theories remain in a biaxial mode, a Y- and a X-axis. Most of these theories date from the previous century and not many new leadership models have been developed during the last few decades. Certainly there has been nothing new since the dawn of the new millennium.

A new leadership postulation is therefore needed to cope with the challenges relating to the 4th Industrial Revolution – one that explains leadership in new and rapidly changing contexts, one that balances work and people with leadership impact, one that has a solid foundation of balance between individual leadership prowess and, finally, one that clearly spells out leadership direction and objectives as a compass to resilience and yet is adaptive and agile.

Beyond the triple bottom line: a new leadership challenge is here

In 2016 the World Economic Forum published online an article written by Alex Gray with the title “The 10 skills you need to thrive in the 4th Industrial Revolution”, this latest revolution being based on the use of cyber-physical systems. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Industrial Revolutions were based on mechanical production equipment driven by water and steam power, on mass production enabled by the division of labour and the use of electrical energy, and on the use of electronics and IT to further automate production, respectively. The ten skills listed by Gray (2016) that are required to thrive in the 4th Industrial Revolution are listed as follows:

- complex problem-solving;

- critical thinking;

- creativity;

- people management (one could read leadership into this as well);

- coordinating with others (group work activities);

- emotional intelligence;

- judgement and decision-making;

- service orientation;

- negotiating; and

- cognitive flexibility.

In another article, published in a local South African newspaper, Beeld, in January 2017 (Maake, 2017) the following were listed as things that machines will not be able to do in future (obviously there could be more). The number in brackets indicates the relative importance of the skill mentioned (1 being most important):

- emotional intelligence (5);

- creativity and innovation (4);

- leadership (3);

- adaptability (2);

- problem solving (1).

From this news article it also indicated the importance of leadership in future and that it will be a key consideration as skill to cope with the challenges associated with the 4th Industrial Revolution (specifically related to the context of the article of what machines will not be able to do).

In Gray’s article people management was listed as the fourth most important skill most likely to be needed, but its importance will probably rise even higher as the 4th Industrial Revolution proceeds. With regard to leadership in the mining industry in particular, a more holistic approach to leadership, and how it will have to be realised, will be needed. Gray’s (2016) article states that by 2020 the 4th Industrial Revolution will have brought us, among others, advanced robotics and autonomous transport, artificial intelligence and machine learning, advanced materials, biotechnology and genomics. The successful implementation of these new developments will require a very different kind of leader. Consequently, the objective of this paper is to investigate and propose the characteristics that will need to be associated with a leader in the 4th Industrial Revolution.

People will have to change and adapt to a new set of skills in order to be successful in the 4th Industrial Revolution. The mining industry is in need of a new generation of innovative complex problem-solvers who also possess the other skills mentioned, and the quality of leaders with a new mind-set and related skills who will have to drive this Revolution will determine the success thereof (Motsoeneng, Schultz & Bezuidenhout, 2013).

The commodity pricing challenges experienced on a global scale in the mining industry in the last decade tested the resilience and endurance of most mining organisations. In South Africa, especially, a number of mining companies had to drastically resize and restructure operations and staff. Future thinking succumbed, expansion plans were shelved and while some companies downscaled some of their operations, others were either taken over or even ceased to operate (Marais, 2013).

Companies that survived and that are just getting over the difficult years are now facing a challenging future with regard to conventional methodologies and thinking, as posed by the current state of our mines and the expected challenges related to the 4th Industrial Revolution. This potentially offers a new future, but also brings new challenges regarding the way in which mining will continue. The Chamber of Mines of South Africa (2017), now the Minerals Council South Africa, indicates that modernisation or next-generation mining will be needed to address rising costs and low productivity. It is therefore obvious that, in this context, the future mine will need a new kind of leadership to restore growth and sustainability in the mining industry. The qualities of mining leadership that will be needed in the future are agility and resilience, to create and maintain a state and culture of readiness (Malnight & van der Graaf, 2011). Companies must adapt to change by adopting solutions and innovations in the areas of robotics, disruptive technologies, new eco-systemic operations, and many more. It will be necessary to extend beyond the current fixed value chains, shifting in knowledge away from production points to off-site trans-organisational knowledge hubs and shared services.

In a 2017 PwC publication titled: “We need to talk about the future of mining” (2017: 18-19), it is stated that: “Technology can become a fundamental success factor. This is a world where ‘leading practice’, not ‘best practice’ is the goal. Rapid advancements in technology – such as robotics, remote operations, drones, machine learning and blockchains – mean the innovations that are cutting edge today might not even exist in five or ten years’ time. So how do you build that flexibility into your mine plan and capital plan (as well as your workforce) if you’re developing a mine that will run for 20 or more years? There is a fundamental mismatch between the lifecycle of mining assets and the lifecycle of technologies and digital enablement that is disrupting the sector”.

Apart from the future of technology in mining, the economic downturn has also exposed leadership in the mining industry – or the lack thereof. Trying to singularly define new horizons of leadership for the future in mining is going to become one of the biggest challenges ever faced (Denton & Vloeberghs, 2003).

Moreover, the future of leadership in mining and other industries alike is going to be very different from what the current traditional hierarchical structures offer. The privilege of rank in an organisational hierarchy, which provides the incumbent with leadership status and a leadership “seat” and its associated command and control authority, has no future in the mining industry. There is therefore a need to rethink the required leadership skills for miners and leaders as perceived and those that are needed to thrive in the 4th Industrial Revolution in many ways that do not exist today. This will, however, be needed within the very near future. Such a rapid ability to change is traditionally not a common characteristic in the mining industry and is less common among current leadership pacemakers in the industry (Schultz & Bezuidenhout, 2014).

Traditionally, the mining industry has developed and entrenched what is a command and control culture. This kind of organisational culture needs urgent transformation. This will be essential to cope with the social and technological demands inherent in future mining operational landscapes, and, as was mentioned before, resilient and agile leadership in the mining industry is urgently needed (Maruping, 2012). History has proved that, over the years, current leadership development practices based on existing leadership theories and models do not provide the required direction for the industry to produce the right skills to meet future leadership demands.

New leadership postulation: the 4.0D Leadership Model for the future

Schultz and Bezuidenhout (2014) ungroup the various leadership clusters and theories into a number of styles, ranging from bottom-up leadership, to transformational leadership, charismatic leadership, authentic leadership and transactional leadership, but they fail to include servant leadership as postulated by Blanchard and Hodges (2003). In analysing the various personality traits of each style, Schultz and Bezuidenhout (2014) clearly follow the path of Trait Theory leadership.

Although these styles and style-specific descriptors come in very handy to describe leadership behaviour, essentially they do not address the fundamentals of leadership. The main reason for this is that a style is an outcome of the function of other human dynamics embedded in the intrapersonal make-up and composition of an individual. Secondly, future leadership requirements tend rather to indicate the need for a new model as a point of departure for formulating a leadership approach. This needs to be independent of a specific leadership style and approach to work and people only – it needs to transcend the biaxial designs of the past.

Currently in leadership development there is a plethora of programmes focusing on a variety of factors that influence leadership, e. g. Emotional Intelligence – commonly referred to as EQ as coined by Daniel Goleman (1995) – and other motivational aspects related to leaders with visionary thinking (Schultz and Bezuiden-hout, 2014). Nicholls (1994) describes a three-tier leadership approach which essentially attempts to integrate the three basic intrapersonal dynamics of individuals: the head, which relates to strategic leadership; the heart, which is linked to inspirational leaders; and lastly the hands, which encompasses the actions and task execution of the supervisory leader. Furthermore, there was a definite trend in the later part of the previous century to focus on leadership styles as a suitable way to analyse how leaders function in organisations. Raza (2019) lists these styles as:

- Autocratic Leadership;

- Democratic Leadership;

- Strategic Leadership;

- Transformational Leadership;

- Team Leadership;

- Cross-cultural Leadership;

- Facilitative Leadership;

- Laissez-faire Leadership;

- Transactional Leadership;

- Coaching Leadership;

- Charismatic Leadership; and

- Visionary Leadership.

Many other leadership styles are also described as leadership solutions for organisations. Most notable of these is Goulston’s (2009) Heartfelt Leadership, which focuses mainly on emotional connectivity between leaders and followers in the form of caring and trust.

All of the above approaches and theories of leadership are very valid and until now served leadership (to a large extent) very well. What is very evident in all these approaches is the “lack of integration of leadership theories and styles”, and this may perhaps be the single element that is missing to bind these leadership theories and styles together. It is therefore suggested that the lack of an integrated leadership model creates diversity in approaches. This diversity is so extensive that the expected future leadership challenges and landscapes may never be addressed in a fitting manner with the required outcomes.

Elements of the 4.0D Leadership Model

Following from the discussions above, an integrated leadership model is now postulated that is independent and not affiliated to any of the leadership theories, and that does not prescribe any leadership style as a single solution. The model is multidimensional and expands beyond the world of work and people only. It links leadership in future contexts and it aligns various, up-to-now isolated, elements in a cohesive manner. The 4.0D Leadership Model is so named because it encompasses the required leadership skills arising from challenges Industry 4.0 brings to people who find themselves in leadership positions. Besides reference to the 4th Industrial Revolution, the “4” of the Model also refer to four main leadership dimensions of the model, namely SELF, WORK, PEOPLE and IMPACT. An exposition of these and their subelements follow.

The Base: where leadership begins – the SELF

Leadership starts with the SELF, which represents the intrapersonal dimension of the leader. The basic components of any individual person lie within a psychological triad referred to as the Three Part Mind (Kolbe, 1990), which states that there are separate domains and capacities, namely thinking, feeling and doing. In more detail, these are:

- (C)ognition: This relates to intellectual functioning. Its taxonomy was first described by educational psychologists Bloom et al. (1956) and 45 years later was revised by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). The taxonomy of the cognitive domain comprises the following (in order of increasing complexity):

- Remembering: Recognising and recalling knowledge from memory, i. e. remembering previously learned information and being able to produce or retrieve definitions, facts or lists from memory.

- Understanding: Constructing meaning from a variety of functions such as written or graphic messages, and activities like interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarising, inferring, comparing or explaining.

- Applying: Executing or implementing using a specific procedure. This step implies situations where learned material is used in products such as models, presentations, interviews or simulations.

- Analysing: Separating information or concepts into parts to determine how various parts relate to or interrelate with one another, or how the parts relate to an overall structure or purpose; also to differentiate, organise and attribute, as well as being able to distinguish between the various parts or components that make up the mental actions of this function.

- Evaluating: Judgement based on criteria and standards by checking and evaluating reports and critiques, recommendations and reports – examples of outcomes that demonstrate the processes of evaluation. In this taxonomy, evaluating is precursory behaviour before something is created.

- Creating: Grouping elements to form a coherent or functional unit or whole. This entails reorganising elements into new patterns or structures through generating a plan or formulating a way forward. It requires that parts are either put together in a new way, or synthesised into a new and different form or product. This process is the highest order of cognition and the most difficult mental function in the new taxonomy.

- (A)ffect: Affective states are a psycho-social construct and “affect” refers to the emotional functioning of the individual which usually “kicks in” before the cognitive process becomes active. It has three basic dimensions:

- Valence: Emotional valence refers to the consequent emotions elicited by a certain situation, as well as emotion-eliciting circumstances (Harmon-Jones, Gable & Price, 2013). These are subjective feelings or affect-based attitudes and may or may not be related to the actual situation – they are subject to the individual’s emotional state and well-being.

- Arousal: This physiological response occurs as an often subconscious response to affective interpretation of a stimulus, and has a scaled result or control mechanism that varies from extreme arousal on the one hand, to complete immobilisation on the other hand (Blechman, 1990).

- Motivational intensity: Gable and Harmon-Jones (2013) found that affective states with high motivational intensity cause a narrow attention scope (a focus ed state with the aim of zooming in on the goal or object needed or desired). Affective states with low motivational intensity cause relatively broad attention scope (a relaxed state in which the scope broadens to seek new opportunities).

- Behaviour ((C)onation): Conation is the third faculty of the mind (Atman, 1987) and is the result of the interactive working of the cognition and affect. It therefore represents the subsequent behaviour – how affect and cognition translate into the individual’s behaviour (Bagozzi, 1992).

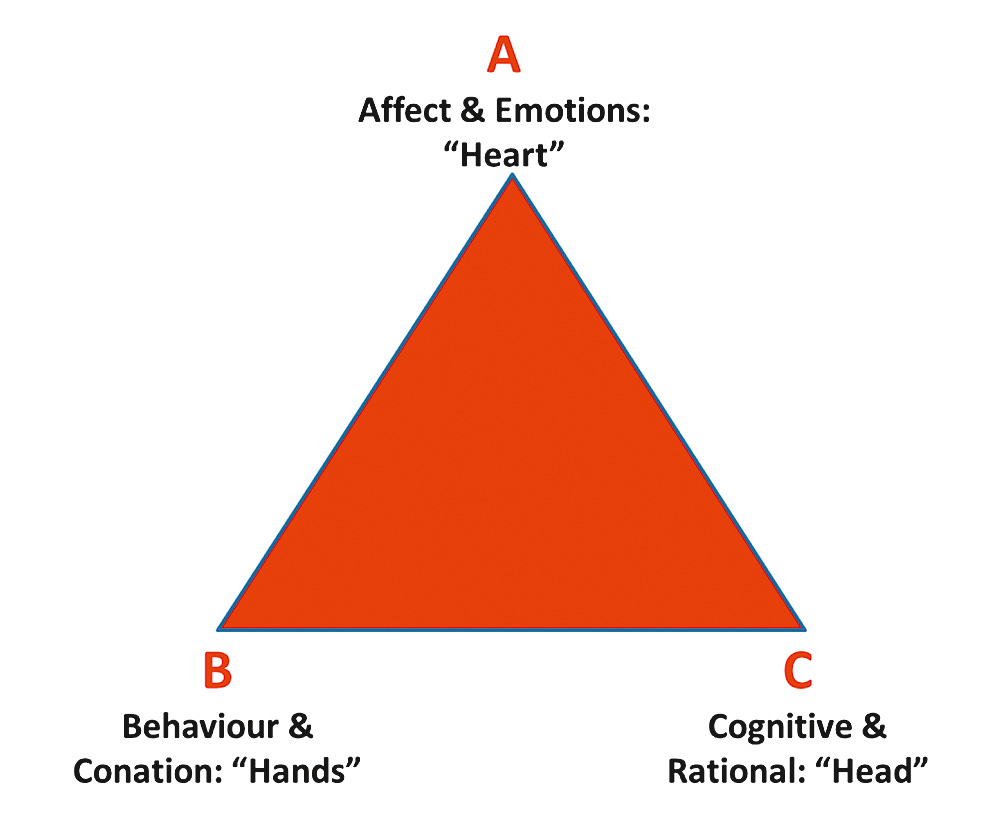

A fundamental principle of the 4.0D Leadership Model is that the interactive balance between the triad of Affect, Behaviour (Conation) and Cognition (the A-B-C) must ideally be perfect – or at least strive to strike a synergistic balance between the aspects of the triad. Hence the assertion as a basic principle of this Model that leadership starts with the notion of SELF, which forms the base of the model as shown in Figure 1.

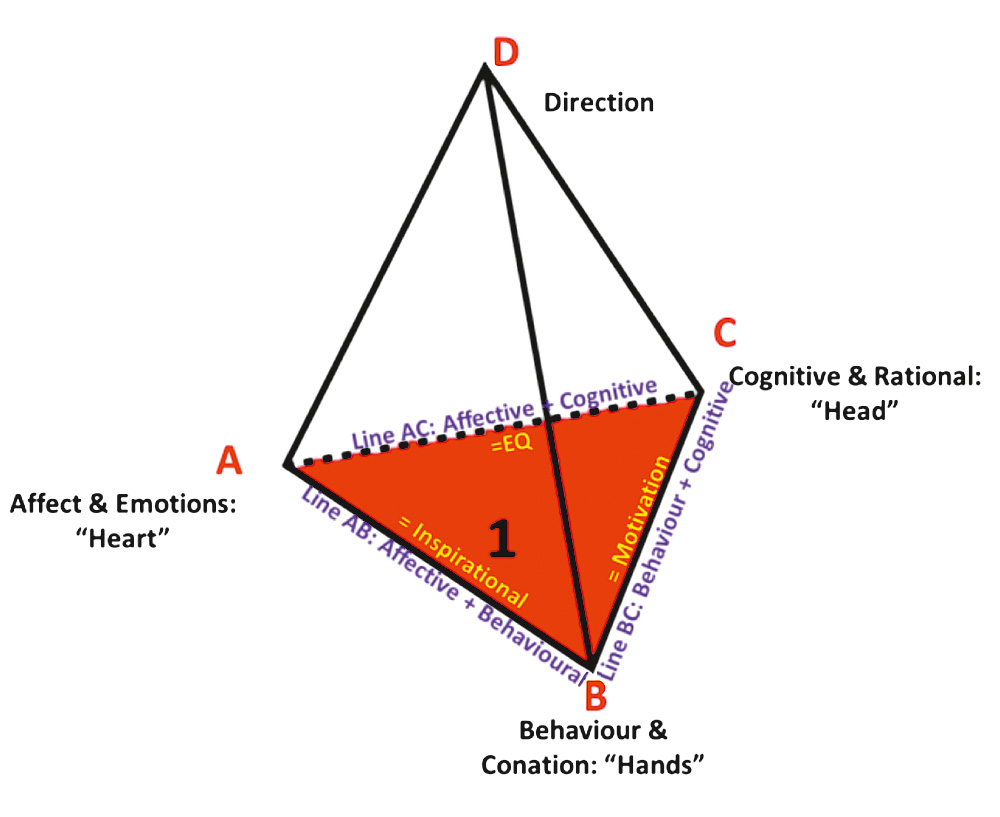

The components of the base, however, do not function in isolation but, as explained in the previous sections, the aspects of the triad of the SELF (A-B-C) interact with each other. An acceptable SELF implies a balanced-based triangle, meaning a congruent condition, and any incongruence implies an imbalance. The base may therefore need intervention to restore the balance and congruency. The lines of interaction are as follows:

- A-B action line: Affect interacts with Behaviour

The outcome of this interaction is widely seen in the domain of the transformational and charismatic leadership styles. The central leadership behavioural theme is inspiration.

- A-C action line: Affect interacts with Cognition

The resultant dynamic of the interaction between rationality and emotion is Emotional Intelligence (EQ field of leadership behaviours). Styles that would fit in this dynamic line could be the authentic leadership and transactional leadership styles. A democratic bottom-up style behavioural continuum would fit in here.

- B-C action line: Behaviour interacts with Cognition

The outcome of Behaviour (conation) combined with the outcome of Cognition (rationality) leads to the arena of leadership motivation (of self, others, units or organisations). The leadership styles that would emerge on the behavioural continuum would be authoritarian and directive leadership styles. These can therefore be illustrated as in figure 2.

The three action lines between the various points in figure 2 contain the essential components, for Motivation, EQ and Inspiration. For leaders to motivate followers, the three part mind elements are Behaviour and Cognition (B-C action line), thus meaning that motivational messages must contain actionable goals and logical sense components.

The EQ action line of the Three Part Mind elements are the interactive outcome of Cognition and Emotion (A-C action line) in the classic Bar-On and Parker (2000) EQ model of (logically and rationally) identifying one’s own emotions, managing one’s own emotions, identifying others’ emotions, and managing others’ emotions.

The Inspirational action line of the Three Part Mind (A-B action line) indicates that in efforts to inspire people, leaders need to combine affective (emotional) components in desired behaviours for the followers to achieve or be “moved” towards being mentally stimulated to do or feel something.

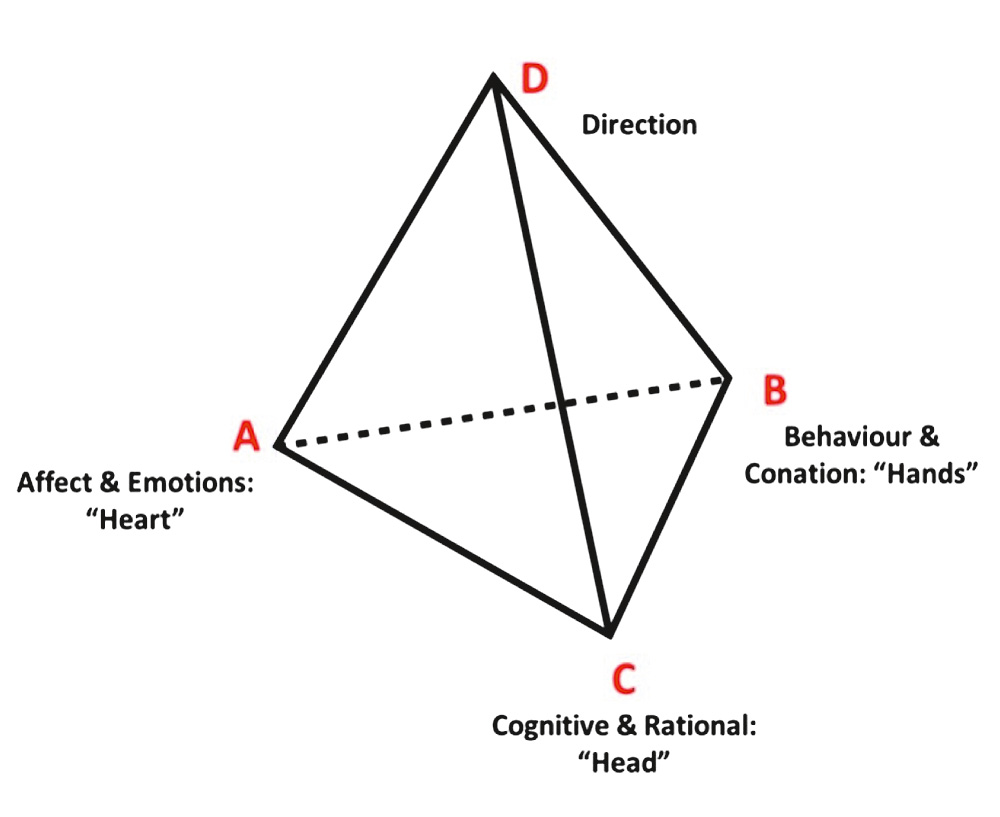

With the base (shown in red and numbered as panel 1 in figure 3) completed, the 4.0D Leadership Model then postulates that from these action lines three “panels” arise to point D and form a tetrahedron (or triangular pyramid), which is illustrated in figure 3.

As a result of the action lines with their associated behavioural continuums, there would be a visible leadership effect of focus. The base creates leadership meaning in three facets in the following manner.

B-C line: Behaviour interacts with Cognition

Leadership manifests in the context of the business environment, internal organisation, the external environment, the business playing field and technical prowess. This panel is termed the WORK panel, shown in purple and numbered as panel 2 (B-C-D), and represents the WORK (vocational) domain, as illustrated in figure 4.

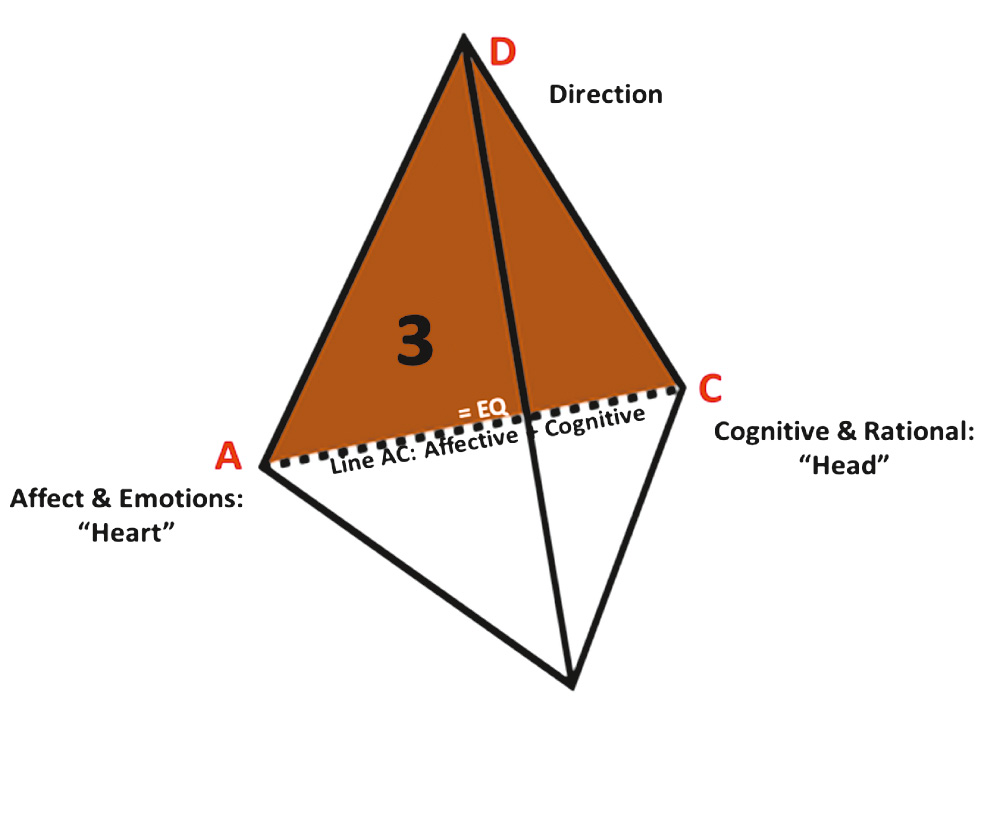

A-C line: Affect interacts with Cognition

The social dimension includes leadership in the context of the -interpersonal domain, with reference to leading people and teams, formal and informal relationships, as well as building organisational culture. Here we refer to “people leadership”. It is termed the PEOPLE panel, shown in brown and numbered as panel 3 (A-C-D), as illustrated in figure 5.

A-B line: Affect interacts with Behaviour

The dynamic line for leadership behaviour related to Affect and Behaviour is known as the IMPACT dimension. It entails leadership in the context of having a meaningful impact on the community, and on internal and external stakeholders – whether they are antagonistic or protagonistic – and alludes to the leader’s legacy on a variety of levels. We refer to this panel as the leadership IMPACT panel, shown in green and numbered as panel 4 (A-B-D), as illustrated in figure 6.

The final component: the Apex

The final component is the Apex (D), whose base is the SELF, which forms the foundation from which the three panels join at the top. All the panels and the base must be in balance for leadership harmony and integration. The Apex of the 4.0D Leadership Model also indicates leadership direction. It represents the unification of the SELF and the organisational direction in the form of the Visionary Futuristic Dimension. This encompasses leadership in the context of the future, with reference to integration between personal and organisational visions, missions and values. The volume within the pyramid also implies increasing levels of leadership complexity. Optimal balance of the pyramid is achieved when leaders within organisations, executives and boards formulate transparent, ethical, principled, virtuous and honest apexes. This reflects a values-driven type of leadership, supported by a sound base and three integrated panels, as illustrated in figure 7.

Recent application developments of the model: direction

Application of the 4.0D Leadership Model in the Southern African mining industry has yielded new developments since it was first postulated in 2017, as described by Uys & Webber-Youngman (2019).

These developments are related to the Apex and specifically the connecting lines of the model between the Apex (D) and the three base lines, namely A-D, B-D and C-D (refer to figure 7).

The Apex and D as direction are labelled as the final component of the model. It has transpired through the application of the model in the last 18 months that leaders often face adversity, opposition, hardship, derailment and obstacles to achieving their goals and objectives, as described previously. It became evident that the first postulation of the model (Uys and Webber-Youngman, 2019) needed expansion to guide and enable leaders to discover their own potentials and capabilities to overcome these negative influencing factors. These lines are termed the “directional support lines” and are elucidated below.

Direction

Direction refers to the notion that leaders give direction as popularly describes as vision and mission; either personal of organisational. However, leaders often encounter hardships, obstacles and setbacks in pursuing their directional goals and for that purpose the model thus includes what is referred to as “Directional Support Lines”. These are presented in the following sections.

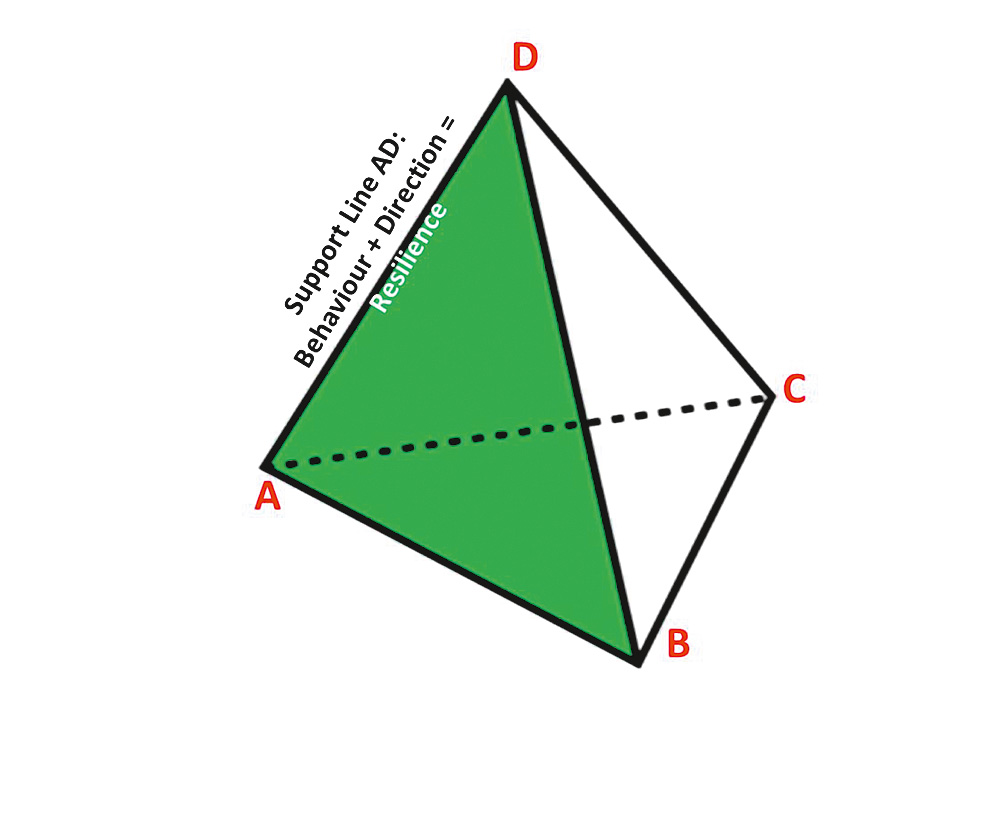

A-D line: Direction – Affect support line

The emotional (Affective) foundation of the A-D line translates into an individual or personal emotional capacity to recover quickly from difficulties and to attain a sufficient degree of emotional toughness. This directional support line is labelled as “Resilience”, as illustrated in figure 8.

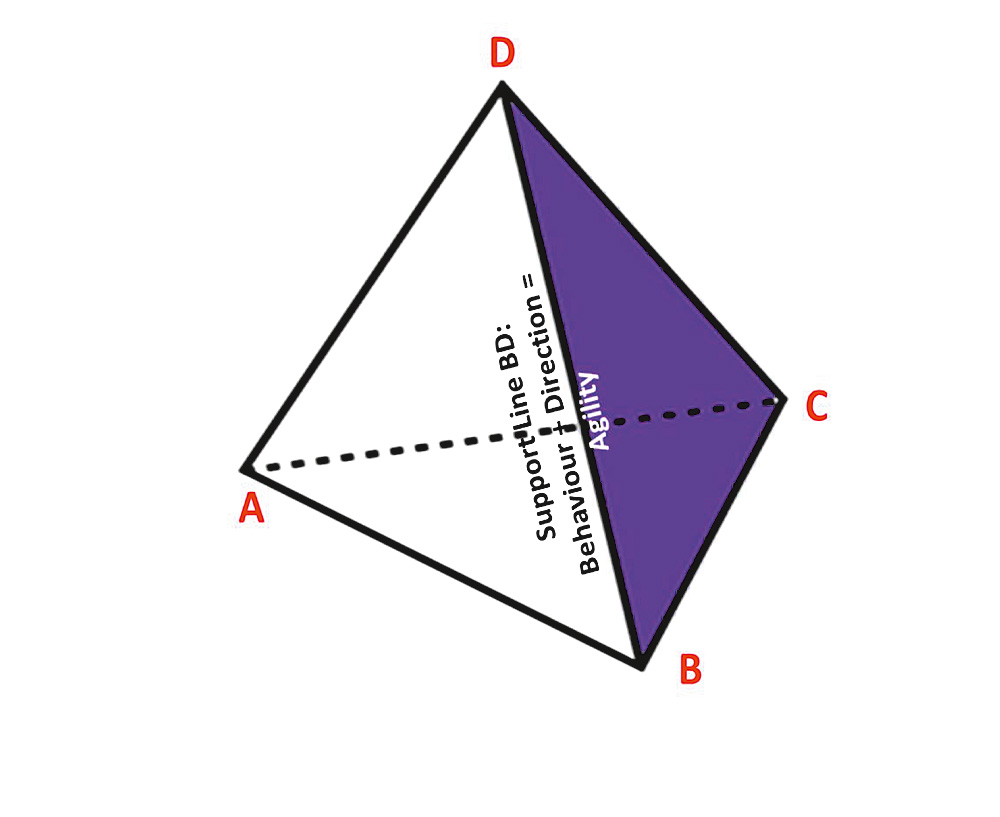

B-D line: Direction – Behaviour support line

Behaviour required to support direction during adversity entails leaders building personal capacity and dynamic capability to demonstrate behaviours that are reminiscent of “making a comeback” in Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous (VUCA) environment/situations and landing on one’s feet when stumbling blocks/obstacles are encountered. This directional support line is labelled as “Agility”, as illustrated in figure 9.

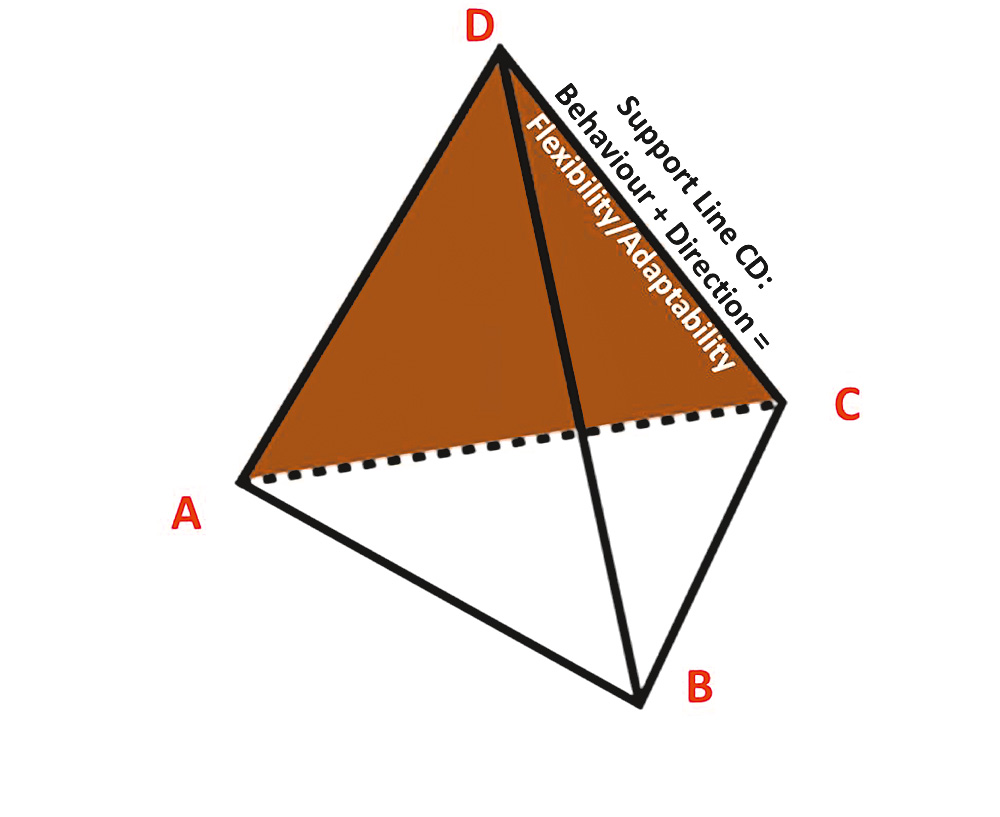

A-D line: Direction – Cognitive support line

The ability to listen and communicate appropriately, to negotiate well, to be open-minded and to consider trends and adapt to changing circumstances demonstrates a sound flexible and adaptable capability, which is required by leaders in pursuance of their directional goals. This directional support line is labelled as “Flexibility/Adaptability”, as illustrated in figure 10.

Understanding the 4.0D Leadership Model postulation

The 4.0D Leadership Model postulated is a model of balance of human dynamics at the Base and of congruence of the rising panels. It integrates a variety of human elements into a working tool for leadership development that needs identification. It could also be used to identify individual leadership flaws and for diagnosing underdeveloped leadership dimensions. If one or more panels are out of balance and/or the base is skewed, sustainable leadership will be adversely affected. An extreme imbalance can even cause the pyramid to topple over and a disintegrating base will cause the “collapse” of leadership.

Congruence between the panels therefore needs constant attention by the leader and by the organisation. This will assist in monitoring the development of the leader and as the complexity of the leadership role changes, the size (“volume” within the tetra-hedron) of the 4.0D model should also change accordingly.

The complexity of change results directly in the changes to the required Apex formulations that the leader must make – thus the Apex of the CEO requires a greater “volume” in the 4.0D pyramid than the “volume” of the middle manager, whose Apex will be tactical as compared to the strategic Apex of the CEO, as illustrated in figure 11.

The 4.0D Leadership Model also aims to integrate a variety of separate points of leadership. While many programmes see EQ, e. g., as the solution to leadership challenges, the contextual fit with other human dynamics is rarely assessed. With the base and three panels (Work, People and Impact), the model offers an integrative approach. Since such an approach also accommodates most of the leadership styles already discussed, it does not exclude any style, behaviour, contingency or trait. Furthermore, the notion of being a leader or not being a leader is really not a choice anymore. As the full impact of the 4th Industrial Revolution unfolds, we envisage that leadership will look differently and that any form or level of decision, work practice and people interaction, will require some form of leadership albeit on various levels and of varying span-width of influence as per the complexity postulation discussed elsewhere in this article.

Application in industry

The 4.0D Leadership Model is a new postulation and is deemed to be epistemologically intact since the design stems from many decades of work in the leadership landscape of specifically the mining industry, as well as the manufacturing contexts. It has been applied for more than a year in a South African gold mining company on three levels, namely Executive, Middle and Senior levels, as well as Emerging and Junior. The initial results seem to hold positive advantages for both individuals and their organisations. Expansion into the aviation industry and the human resources fields is being investigated, as well as into the copper and platinum mining industry globally.

Conclusions

- It is evident that historically there were several different types and theories of leadership style, each specific and relevant in terms of its timeline in history.

- In terms of the challenges associated with the 4th Industrial Revolution and its expected complexities, a new type of leadership model was needed.

- The elements of the new 4.0D Leadership Model include a base (SELF), which represents the intrapersonal dimension of the leader, and three panels (WORK, PEOPLE and IMPACT), making up a triangular pyramid or tetrahedron.

- The basic components of any individual (or the SELF) lie within the psychological triad of Affect, Conation (Behaviour) and Cognition – the Three Part Mind approach.

- A fundamental principle of the 4.0D Leadership Model is that the interactive “balance” between Affect, Behaviour and Cognition (the A-B-C) must ideally be perfect – or at least strive to strike a synergistic balance between the aspects of the triad – hence the assertion that leadership starts with the SELF (the base of the model).

- The 4.0D Leadership Model is the first model in leadership that integrates several free-standing leadership compass points into a cohesive unit and places various important leadership requirements, such as EQ, Inspiration and Motivation, in its context via the action lines. These provide leaders with a clear “plan” or methodology on how to achieve these requirements for leadership because the major elements are clearly defined.

- Through the directional support lines, the 4.0D Leadership Model also clarifies the place of and the need to develop new psychological “states of mind” for leaders and approaches to overcome adversity and obstacles in pursuing their personal and vocational visions and aspirations. This is needed in a VUCA world through building resilience, practising agility and achieving better states of flexibility and adaptability.

- The 4.0D Leadership Model postulated is a model of the balance of human dynamics at the base and of congruence of the rising panels. It integrates a variety of human elements into a working tool for identifying individual leadership flaws and for diagnosing underdeveloped leadership dimensions.

- The complexity of the changes taking place with new increased levels of leadership responsibility results directly in the required changes to the Apex formulations that the leader must make.

- It is the belief of the authors that the 4.0D Leadership Model should be implemented at academic institution level as well so as to prepare future generations in dealing with the complexities associated with the 4th Industrial Revolution.

It was highlighted above that, historically, the mining industry has developed and entrenched what is a command and control culture. It was also stated that this kind of organisational culture needs transformation. This is essential to cope with the social and technological demands inherent in future mining operational landscapes, specifically with regard to sustainability and agility in terms of leadership.

It was furthermore stated that the challenges associated with the 4th Industrial Revolution will in future need a different kind of leadership model. The 4.0D Leadership Model postulation, through its multidimensional and integrated approach in terms of leadership development, offers a potential solution to addressing the leadership challenges facing the mining industry in future.

Suggestions for further work

Due to the novelty of the model proposed, it is in the process of being tested and applied in the mining industry. It is therefore implied that this model will be appropriate for the mining and other industries and will be tested in terms of its applicability and its successful implementation, and that adjustments may have to be made.

References

References

Anderson, L. W.; Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001): A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Atman, K. S. (1987): The role of conation (striving) in the distance education enterprise. In: American Journal of Distance Education, 1(1), pp 14 – 24.

Bagozzi, R. (1992): The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. In: Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), pp 178 – 204.

Bar-On, R.; Parker, J. D. A. (Eds.) (2000): The handbook of emotional intelligence: The theory and practice of development, evaluation, education, and application – at home, school, and in the workplace (1st ed). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bezuidenhout, A.; Schultz, C. (2013): Transformational leadership and employee engagement in the mining industry. In: Journal of Contemporary Management, 10(1), pp 279 – 297.

Blanchard, K.; Hodges, P. (2003): The servant leader. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Blechman, E. A. (1990): Moods, affect and emotions. Hillsdale, NJ. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bloom, B.; Englehart, M.; Furst, E.; Hill, W.; Krathwohl, D. (1956): Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green.

Chamber of Mines of South Africa (2017): Modernisation: Towards the mine of tomorrow. Fact Sheet 2017. Johannesburg.

Denton, M.; Vloeberghs, D. (2003): Leadership challenges for organi-sations in the New South Africa. In: Leadership & Organization Development, 24(2), pp 84 – 95. doi: 10.1108/01437730310463279.

Edwards, L. (2010): Ronald Reagan and the fall of communism. The Heritage Foundation, USA. Retrieved from www.heritage.org/report/ronald-reagan-and-the-fall-communism

Elkington, J. (2018): 25 years ago I coined the phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harvard Business Review, 25 June 2018.

Gable, P. A.; Harmon-Jones, E. (2013): Does arousal per se account for the influence of appetitive stimuli on attentional scope and the late positive potential? In: Psychophysiology, 50(4), pp 344 – 350.

Goleman, D. (1995): Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

Goulston, M. (2009): Just listen: Discover the secret to getting through to absolutely anyone. New York: AMACOM.

Gray, A. (2016): The 10 skills you need to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

Harmon-Jones, E.; Gable, P. A.; Price, T. F. (2013): Does negative affect always narrow and positive affect always broaden the mind? Considering the influence of motivational intensity on cognitive scope. In: Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(4), pp 301 – 307.

Kolbe, K. (1990): Conative connection. Boston, MA: Addison Wesley Longman.

Lonmin Platinum (2012): Sustainable Development Report for the year ended 30 September 2012. Retrieved from http://sd-report.lonmin.com/2012/people-planet-profit

Maake, I. (2017): Take wat nie deur’n masjien gedoen kan word nie (Tasks that cannot be done by a machine). Beeld, 23 January 2017, 4.

Malnight, T.; van der Graaf, K. (2011): Leadership challenges in South Africa: A land of contradictions. Leading in a Connected Future (LCF) Insights #2011-004. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org

Marais, L. (2013): The impact of mine downscaling on the Free State goldfields. In: Urban Forum, 24, pp 503 – 521. doi:10.1007/s12132-013-9191-3.

Maruping, P. (2012): The Mining Sector Innovation Strategies Implementation Plan. 2012/13 – 2016/17. Pretoria: Technology Innovation Agency.

Matthews, G.; Deary, I. J.; Whiteman, M. C. (2003): Personality traits (2nd ed). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Motsoeneng, L.; Schultz, C.; Bezuidenhout, A. (2013): Skills needed by engineers in the platinum mining industry in South Africa. UNISA. Retrieved from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13876/13R0045M%20Picmet%20Artikel_Motsoeneng.pdf?sequence=1

Nicholls, J. (1994): The “heart, head and hands” of transforming leadership. In: Leadership & Organization Development, 15(6), pp 8 – 15.

PwC 2017: We need to talk about the future of mining. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/energy-utilities-mining/assets/pwc-mining-transformation-final.pdf

Raza, A. (2019): 12 different types of leadership styles. Retrieved from https://wisetoast.com/12-different-types-of-leadership-styles

SAMERDI (2017): Project Charter: Human Factors of the South African Mining Extraction, Research Development and Innovation (SAMERDI) strategy. Johannesburg.

Schultz, C.; Bezuidenhout, A. (2014): A leadership initiative to enhance employee engagement amongst engineers at a gold mining plant in South Africa. UNISA. Retrieved from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13883/Picmet%20artikel%20Leadership%20initiative%20_Anglo.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Scouller, J. (2011): The three levels of leadership: How to develop your leadership presence, knowhow and skill. Kemble, UK: Management Books.

Smit, P.; Cronje, G. J.; Brevis, T.; Vrba, M. J. (2013): Management principles: A contemporary edition for South Africa (5th ed.). Cape Town: Juta.

Spillane, J. P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J. B. (2004): Towards a theory of leadership practice. In: Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), pp 3 – 34. doi:10.1080/0022027032000106726

Uys, J.; Webber-Youngman, R. (2019): A 4.0D leadership model postulation for the Fourth Industrial Revolution relating to the South African mining industry. In: Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. DOI ID: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/17/450/2019. ORCiD ID: https://orchid.org/0000-0002-5046-8934